Significant and Insignificant Mounds

Jennifer Colten and Jesse Vogler

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled I) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Whereas we would have once looked to the natural ecology of place for meaning, and subsequently to systems of land division and settlement, it is in the landscape typology of the mound that the American Bottom most clearly enters the field of legibility. This region is rightly celebrated as the center of a vast civilization that had as its central architectural and urban expression the construction of mounds. Mound complexes from the well-known Cahokia Mounds to the lesser-known Pulcher and Grassy Lake sites remain the defining signifiers of a long and advanced era of North American settlement.

Yet the construction of mounds continues. Mound building has, if anything, even increased. While the civic and cosmic ordering that animated so much of the Mississippian era mound builders has, in this new era of mound building, been sidelined for the logistical and the proximate, our contemporary mounds index a way-of-being no less profoundly than the artifacts of the mind builders of pre-history. Slag heap, salt dome, aggregate piles, landfill, mulch mound—these are the forms of our cosmologies.

Which is to say, in landscape, it all matters. It all has meaning.

This is an itinerary of Significant and Insignificant Mounds of the American Bottom.

It is oriented to an intentional flattening of signification—where meaning mingles uneasily with form. It puts us in proximity of meaning, without being identical to it. The value judgments suggested in our title do not cut along easy lines. For in the end, each of these mounds is, on its own terms, both significant and insignificant. They are all markers to a way of being, a way of seeing the world. Our interest in the pairing of text and image, and in the pairing of so-called meaning-filled and meaning-less subjects, is to bring the process of signification itself to the surface, in order to complicate received value judgments that so often attend landscape photography and description.

The American Bottom is a particularly prolix landscape—with an archive of written description that stands in marked contrast to its relatively unknown status today. From the early notebooks of Jolliet and Father Marquette, to the French Jesuit monks who set up parishes in the region, through the Early Republic notebooks of both William and George Rogers Clark, and forward through the 19th century expeditions—this is a landscape that has been cast in the net of language for centuries. Yet we are keenly aware that it is only since European settlement that this landscape has been made to ‘speak’. And it is here where our photographs put forward an argument for artifacts as evidence—artifacts that index a way of being and which carry meaning and value across discursive registers. Indeed, it is through a measured approach of adesignation, the intentional misalignment of image and referent, that Significant and Insignificant Mounds frames an irreducible landscape form—neither subject to appropriative reverence nor declinist narratives.

Among the many voices coaxing this irreducible landscape into the order of language, we might look to Edmund Flagg for one of the earliest and most comprehensive descriptions. Writing from the edge of Monk’s Mound in 1837, Flagg gives voice to the mingling of cultural and natural landscapes that define the American Bottom:

The view from the southern extremity of the mound, which is free from trees and underbrush, is extremely beautiful. Away to the south sweeps off the broad river-bottom, at this place about seven miles in width, its waving surface variegated by all the magnificent hues of the summer flora of the prairies. At intervals, from the deep herbage is flung back the flashing sheen of a silvery lake to the oblique sunlight; while dense groves of the crab-apple and other indigenous wild fruits are sprinkled about like islets in the verdant sea. To the left, at a distance of three or four miles, stretches away the long line of bluffs, now presenting a surface marked and rounded by groups of mounds, and now wooded to their summits, while a glimpse at times may be caught of the humble farmhouses at their base. On the right meanders the Cantine Creek, which fives the name to the group of mounds, betraying at intervals its bright surface through the belt of forest by which it is margined. In this direction, far away in blue distance, rising through the mist and forest, may be caught a glimpse of the spires and cupolas of the city, glancing gayly in the rich summer sun. The base of the mound is circled upon every side by lesser elevations of every form and at various distances. Of these, some lie in the heart of the extensive maize-fields, which constitute the farm of the proprietor of the principal mound, presenting a beautiful exhibition of light and shade, shrouded as they are in the dark, twinkling leaves. The most remarkable are two standing directly opposite the southern extremity of the principal one, at a distance some hundred yards, in close proximity to each other and which never fail to arrest the eye. There are also several large square mounds covered with forests along the margin of the creek to the right, and groups are caught rising from the declivities of the distant bluffs.

Today, standing atop the visitor-worn surface of Monk’s Mound, we might be more likely to take note of the hulking mass of Milam Landfill directly to the west, or the brown smoke-filled horizon of US Steel to the north, or, until very recently, the twin stacks of the former Armour Plant of National City. Look hard enough, and we might be able to re-train our eye to see the meander scars and lowland forests that still define the creek margins of Flagg’s description. Even though those creeks no longer flow and have been channelized by canals and ditches over the past century, the floodplain of the American Bottom retains traces of its lacustrine past, just as the array of mounds, now sharply delimited by the lawn mowing regime of the State Park maintenance staff, remind us that, despite the destruction of a large number of mounds in the period of industrial and infrastructural growth, markers to prior inhabitation remain numerous.

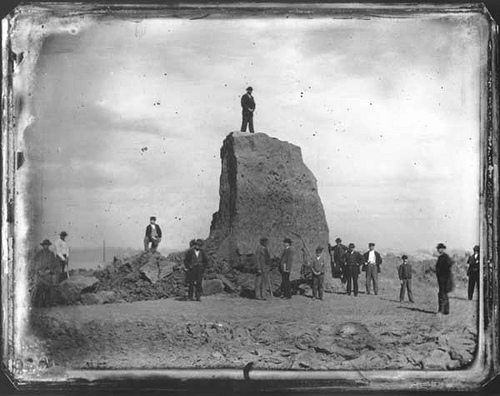

Yet the provenance of pre-contact mounds has not always been so unambiguous. Up until the early 20th century, it was common enough to find, in scholarly reviews and articles, suggestions and arguments as to the natural origin of the mounds. It was as if the ideological barriers to accepting the creative and constructive capacity of pre-contact Native Americans was too great an intellectual burden for anthropologists to bear. As only one example, we might cite the paper titled “Origin of Monks Mound,” given in Philadelphia at the 1914 Geological Society of America meeting by Dr. A. R. Crook, in which he writes: “It may be well to inquire if all so-called mounds in the Mississippi Valley are not natural topographic forms.” And where, 8 years later, he recapitulates, in no less an authority than the celebrated journal Science, the position that a recent study “establishes, beyond doubt, that [Monks Mound] is not of artificial origin, as has been so generally held but that it is a remnant remaining after the erosion of the alluvial deposits, which at one time filled the valley of the Mississippi, in the locality known as the “Great American Bottoms.” Wind-blown piles of loess; aggregated sediment from eddying currents of the river; or simply the remainder of even-larger mounds eroded by the regular flooding of the Mississippi—the theories of the Mounds origins seem to more easily imagine a natural world full of creative agency than a native peoples summoning of order and meaning.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled III) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Alternatively, alongside this topographic framing, a parallel narrative emerged further divesting the agency of contemporaneous Native American predecessors—the Mound-builder myth. One no less influential than Noah Webster described, in 1788, the Ohio River mounds as the work of “Carthaginians or other Mediterranean nations.” With this, archeologist John Kelly writes “the beginning of the “Mound-builder” myth were carefully being sown in the fertile minds of the American Public.” This broader attitude can perhaps be understood as a symptom of the so-called Theory of Two Civilizations—the theory that, prior to exploration and inhabitation by Europeans in historic time, there must have been two distinct epochs of human habitation of the Continent. The inability of a European settler consciousness to imagine and accept the Mounds as a product of the indigenous peoples or their immediate forbears led not a few to posit an “Extinct Race” of people that inhabited the territory and left these material traces of their civilization. Yet then there are others, for whom the Mounds display little more than an innate animal consciousness. Lucien Carr, a significant figure in turn of the century archeology and Assistant Curator of the Peabody Museum of American Archeology and Ethnology, somewhat apologetically writes: “as a matter of fact, the ant hills of Africa, in point of relative size, and in the architectural knowledge and engineering skill displayed in their construction, are quite equal to any earth-work in the Ohio Valley.”

Where, then, is the threshold for mound-ness to be found? As an early geologist of the Mound groups of the American Bottom noted in 1922: “Practically all of the mounds which are large enough to attract attention have a distinct artificiality in their regularity of form and steepness of slope.” Which is to say, in the eye’s catalog of forms, it is a particular angle of repose, a ratio of figuration, which enters a mound into the field of the remark-able. But when compared to the complexes that enliven a kind of global pyramid consciousness, what distinguish the Cahokian mound group are its blunt, earthen edges. Rather than the sharp stonework of the Temple of the Sun and Moon, Monk’s Mound is constructed entirely of dirt and is currently covered in a wooly sheet of grass and weeds. The mounds surrounding the main ceremonial center are likewise carpeted in turf and most distinctly enter the field of legibility immediately following their bi-weekly lawn mowing. It is in this bright line of demarcation, in the contour and mowing decision of the maintenance crew, that Cahokia reaches its architectural apotheosis.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled I) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

What do we get by following the piles? By attending to this base ordering of matter? It is my belief that there is a counter historiography that can be written that traces the mound as the originary architectural gesture. A mark with meaning. An alternate tectonic myth grounded in the recognition of earth out-of-place. Adolph Loos, in recognizing the unadorned, psychological power of the mound, writes: “When walking through a wood, you find a rise in the ground, six foot long and three foot wide, heaped up in a rough pyramid shape, then you turn serious, and something inside you says: someone lies buried here. That is architecture.” Architecture as a recognition of matter out-of-place; of matter in particular arrangement; of an affective register of arrangement.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled I) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

But for every pile, there is a pit. And we would do well to not let the formal legibility of the mound distract us from the fundamental transactional economy in this (dis)ordering of matter. Lewis Mumford, that scion of urban meta-narratives, reminds us that the quarry pit is characteristic of the process of Abbau, or un-building: “What is taken out of the quarry or pithead cannot be replaced.” And so, with the borrow pits that ring Cahokia Mounds State Park, the regular, rectangular water bodies that lie adjacent to highway construction, and the hundreds of mines and quarries that lie out of eyeshot, we must be attentive to the reordering of earth that gives us all of our mounds. In this, we can read the mound as a transitional object. As the becoming-city. For it is in the hundreds of unremarked piles of limestone, earth, mulch, and sand, and their parallel constellation of pits, that our roads, buildings, sidewalks, and parks are aggregated and extracted.

But perhaps our mounds are no less enigmatic. After all, who, really, can account for the otherworldly, colorful mound sitting across the river just south of the gateway Arch? That reliable sources tell me it is a heap of the residue left after the burning of coal does not explain the range of reds, browns, blues, and yellows that marble its surface—let alone begin to answer what it is doing in the floodable part of the floodplain. I have revisited this mound dozens of times, and each visit reveals a new silhouette, a new stratum, a new rent carved by the most recent rain or flood.

I know all the constituent parts of this mound—the Fe, the O2, the Pb. I will never understand this mound.

It eludes me in its significance.

Wood River Power Plant

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled I) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Grassy Lake

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled X) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Adjacent to the baseball diamond and park structures of the South Roxana Dad’s Club Park sits the last remaining intact mound of the Grassy Lake Site. Standing on the west edge of the park, along Old Edwardsville Road, you can discern a distinct topographic rise—running NW-SE—on which the mound is situated. This rise is part of the Wood River Terrace, which formed the northeastern edge of the former Grassy Lake. Like many of the other American Bottom mound complexes this is a lacustrine mound group, positioned adjacent to a water body formed from a former channel of the Mississippi. Identified as Mound #10 in archeological reports, this mound was on the south end of a string of mounds that were located along the Wood River Terrace reaching up to the present day Refinery Museum.

Unlike the Cahokia, St. Louis, East St. Louis, and even Pulcher sites, this northern complex was not situated near any heavily trafficked Colonial era trails and roads and, as such, remained un-remarked upon for longer than many of the mound groups. Interestingly, the first known description of these mounds comes to us from William Clark—who explored the area in the winter leading-up to the great Army Corps of Discovery Expedition later known as the Lewis and Clark expedition. Departing the winter Camp Du Bois at the mouth of Wood River on a cold January 9, 1804, Clark traveled east across the icy bottomland wherein he “discovered an Indian Fortification,” continuing: “In this fortress is 9 Mouns forming a circle two of them is about 7 foot above the leavel of the plain on the edge of the first bank and 2 M from the Woods & about the Same distance from the main high land” [sic]. We have in this description as much a recounting of the mounds as a narration of the geography of the region—with its terraces, woods, lake, and banks.

Chemetco

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled VII) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

This 14 acre pile is the slagheap produced by the adjacent Chemetco plant—at one time the largest secondary copper refinery in the country. Despite its dead, scorched aspect, this is heap of matter rich in secondary materials. With the company and its property in receivership, the current owners are looking to extract latent metals to be sold to help pay for site cleanup and to cover prior debts. Mound as a geologic bank account.

EPA reports estimate the mound to be composed of 836,653 tons of air-cooled slag, with elevated levels of lead and copper that fails the Toxic Characteristic Leaching Procedure hazardous waste tests. For reference, the health-based benchmark for lead is set at 400 parts per million, while certain piles on site were found to have up to 139,000 parts per million. Industrial sprinklers work 24/7 to abate potential dust from this 13 acre mound escaping in to the atmosphere, while holding ponds impound runoff to keep it from entering Long Lake. While its form may be gradually reprocessed as the site nears EPA mandated closure, its component parts—heavy metals, dioxins, and PAHs—will remain a signal part of the muddy substrata of the bottoms for all time. One of the many contributors to the anthropocenic geological record of the American Bottom.

Kerr Island

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XI) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Kerr Island Text Here.

Old American Zinc

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled II) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

This is a 5-acre mound composed of the vitrified slag from the zinc refining process. Old American Zinc operated its primary zinc smelter facility on the site from 1912 until 1967, when it was courted by the entrepreneurial industrial municipality of Sauget and moved its operations there. This lead laden heap sits surrounded by the community of Fairmont City—a community once reliant on the plant for employment. In one of the more penetrating social narratives of recent American Bottom history, following a prolonged strike at the plant in 1918, American Zinc looked beyond the borders of the US for a culturally homogeneous workforce in what Andrew Theising has described as a ‘social experiment’ in factory management. Looking to break the strike, American Zinc imported worker from Mexico, thinking that by sourcing workers en mass, the company would be more likely to maintain its work force. Not only was this the case, but this community has outlived its employer. Fairmont City has the highest percentage of Hispanics in the St. Louis Metro area with at least 71% of the population of Hispanic descent—marking a pattern of migration that began in 1918 and continues today.

Beginning in 1976, after the site sat idle for a decade, new owners began crushing the slag material to use as fill and leveler to construct a new intermodal operation on the site. Based on an EPA study, there is an average of 3.5’ of this ground slag material spread across the 90 acres of the site. Additionally, and tragically, this material was trucked offsite to be used as fill and base material for road and building projects elsewhere—leading to an unknown spread of the contaminated material into surrounding communities. With this potential cross-site contamination, the EPA officially listed the Old American Zinc plant to the Superfund National Priorities List in April 2016. They have yet to develop either a systematic or ethical abatement strategy addressing the wider Fairmont City and its inhabitants.

Milam

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled V) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Travelers heading east across the Mississippi from St Louis would be forgiven for confusing the Cahokia Mound complex with its much larger cousin—the Milam Landfill. Situated less than 3 miles away and due west of Monk’s Mound—directly on the path of the setting sun—this modern-day mound is still in the process of construction. Receiving waste from across the St. Louis metro region and from sites as far away as Iowa and Indiana, Milam is the shadow impulse of mound-building writ large across the 20th century industrialized landscape of the American Bottom.

Milam is situated in a former wetland formed in the gradual meander of the Mississippi some 1000 years ago. Up through the 20th century, Cahokia Creek—the Bottom’s most significant watershed—crossed this spot in its circuitous path from bluff to river. Channelization rerouted the Creek to the north just as another ditch drained what remained of Indian and Canteen Lakes—in a engineered sequence that ‘opened’ the wetlands of this area to large-scale development. Though new extensions to Milam have an up-to-date liner, earlier dumping in the area does not have such a barrier. Today, the landfill stands adjacent to the few remaining, and compromised, wetlands around the former channel of Cahokia Creek as well as the bowl of the Gateway Motorsports Park. Milam and Gateway sit in a mirror relationship—one concave, the other convex;

Here we have a landfill not simply as midden heap, but as oracular assemblage. Composed of offerings from hundreds of miles distant. There is no doubt that our mounds will themselves be subject to the probing inquiries and contradictory theories of future inhabitants. Only here, the inevitable search for meaning may have to lie in the plastic lawn chairs and Busch Lite cans that will certainly remain.

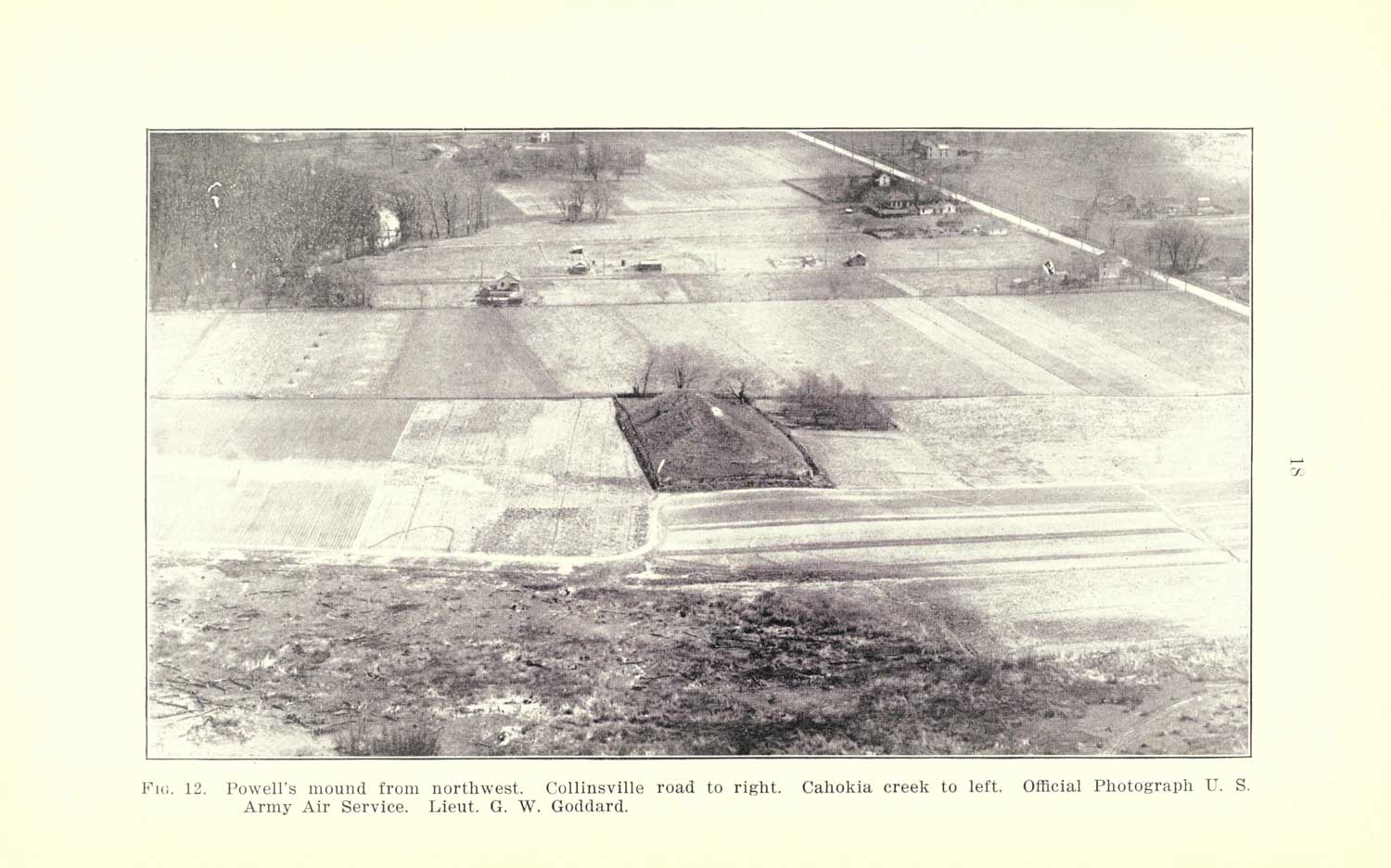

POWELL | WILSON | SAM CHUCALLO

Driving along Collinsville Rd. adjacent to Fairmont City is a distinct topographic transition marking the edge of the former Indian Lake. To the North, one can detect a noticeable drop in grade—with the marshy lowlands of the lakebed still legible between the trees and reeds. Here, along this small ridge formed by the natural levee formed by the ancient river meander, was a string of Indian mounds—Powel, Wilson, and Sam Chucallo Mounds—that were part of the larger Cahokia polity. Extending along an ancient causeway connecting Cahokia with East St. Louis that followed this ridge, these mounds have been for the most part destroyed; lying, as they were, on the outskirts of the more charismatic clustering at what would become Cahokia Mounds State Park. Taking cues from the natural topographic rise of the natural levee, pre-contact Native Americans sited a series of burial and other mounds on land held up out of the flood prone area below. In this, we can detect a fundamental human pattern of site selection. No human, ever, it seems, likes to build in swampy areas.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XV) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Powell Mound was of particular interest to early archeologists—as it was the second largest of the Cahokian precinct mounds. Yet the relentless mound-removal of the late 19th and 20th centuries left this large tumuli flattened. In late 1930 and early 1931, surrounded by a group of spectators and an occasional archeologist, a steam shovel dug away at the body of this mound, revealing, then destroying, a large group of elite burial sites. The Powell family reportedly had a standing offer of $3000 for any group that wanted to save the mound for preservation and exploration, but when no group stepped forward, and following rumors of the impending use of eminent domain, the family moved ahead with clearing the mound for agricultural purposes and to fill in low spots elsewhere on their farm. Work dismantling the mound started on the north side of the mound, with the steam shovel out of view from the highway and hidden by the massive mound, and proceeded for over a week before the public was aware that demolition had begun. Today, the site is marked, we might say, by the itinerant businesses that inhabit the large strip mall of the former Gem International Inc. store and parking lot at the Northeast corner of Collinsville Rd., Kingshighway, and State Route 111.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XIV) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

While one might take the “Indian Mound’s Hotel” as one of the many naming ploys trying to cash-in on the nearby Cahokia Mounds Park, it in fact sits on the site of the former Wilson Mound. The first recorded archeological investigation of this site was conducted by Preston Holder of Washington University who, despite calling this site the “junk-yard site,” uncovered here significant burials.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XVI) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Adjacent to one of Fairmont City’s most popular Mexican restaurants sits the Sam Chuallo Mound. Named after the early 20th century landowner whose personal perseverance preserved the mound, the mound is part of the distributed State Park system. In a technique common through the area, the mound is contained in a low chain-link fence. It is as if the vital, chthonic energies that inhere in the mound must be caged.

CAHOKIA

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled IV) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

The mounds of Cahokia are some of the few remaining mounds in the region that survived the massive 19th and 20th century industrialization of the floodplain. The region was historically scattered with such complexes, but their consolidated earthen forms proved too alluring for developers and municipalities eager for fill-material—and they were scrapped and carted away to build the cities and roads—such as the one that bisects the site today.

The network of hundreds of mounds were seen, by an enormously ‘productive’ and aggressive anglo-settler population, as ready fill material for the railroads and towns and building sites that were elevated above the flood plane by excavating and reallocating the earth from the mounds. These mounds were artifacts that were both celebrated and erased simultaneously—in what contemporaneous authors described as capitalism’s cycle of creative destruction. Mounds were leveled. Factories were built. Roads and buildings were named after the mound features they replaced. With this, 90% of the mounds and the immediately visible traces of Cahokian era settlement were erased. Seemingly.

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XIV) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Additionally, the Cahokia mound group itself has undergone a number of shocking and ignoble re-inhabitations—first as the site of a Trappist monastery (from which Monk’s Mound gets its name), and subsequently as a drive-in movie theater and site of a large, 1940’s tract-home subdivision. This subdivision prompted the call for a WPA group of archeologist to conduct initial study of the Cahokia site, but following the bombing of Pearl Harbor the following year, all archeological work was suspended and would not recommence until the mid 1950s. It was here, in 1960, that the new Federal policy mandating that an archeological inventory be conducted prior to construction of any Federally funded roads, was tested on a large scale. This sort of ‘salvage archeology’ is one of the many paradoxes of American Bottom narrative recovery: it is only through a process ultimately destructive to the site that any funding for work and recovery can be secured.

Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption

Nestled between burial mounds and chthonic axes were dozens of vinyl sided houses. And when the Mounds Drive-In began to loose viewership, it was transformer into an X-rated movie park—where advertisements announced “NOW!....FOR THE FIRST TIME…..SHOWN TO ADULT MALE AND FEMALE AUDIENCES TOGETHER! SEE IT….DISCUSS IT…In The Complete Privacy of Your Automobile!!”. They may have added: “IN THE SHADOW OF THE COUNTRY’S LARGEST INDIAN MOUND!!”

Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption Caption

In the 1980s, the state of Illinois began to purchase the land under this subdivision and drive-in. While the buy-out stopped short of explicitly invoking eminent domain, there remain numerous holdouts to the expanded aspirations of the State Park. Over the next decade, state park and preservation groups scraped clear most signs of the homes and infrastructure that once inhabited the cosmic axis, and initiated the carpeted lawn planting scheme seen today.

In discussion with the State of Illinois Extension Agency, archeologists and geologists decided on a Brome Grass as the choice specimen for exclusive and extensive propagation. The plantings they chose had to walk a fine line of stabilizing the earth while not having an intrusive root system that might disturb artifacts buried below. Trees, for the archeologist, carry the threat of loss of information—as their root growth scrambles the layers and material that makes excavation legible. Much more promising for is a parking lot.

Such is the paradox of preservation.

Yet beneath the neatly trimmed grass of the State Park and between the park-like distribution of mature trees, one can still discern the pattern of sidewalks, power-poles, and house-lots that once delineated this site. Descending the XXXX steps of Monks Mound, crossing Collinsville Ave, and continuing south along the central axis of the park, the visitor can here pick out the distinct crown of mid-century road construction. In place of curb and gutters are shallow ditches, still carrying away surface water to the sunken borrow pits further to the south. And in a sort of double cosmic retribution, or an ecumenical nod to preservation’s contracting horizon, a single, green-vinyl-sided tract home remains. Perhaps it is here, in the constellation of prehistoric mounds, industrial landfills, and post-war housing, that preservation can ask its most potent, and troubling, questions.

North ALCOA Site

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XIX) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Known by its EPA nom de plum, the North Alcoa Site is a National Priorities List-caliber site that is being managed through a Superfund Alternative Approach--which has the towns of East St. Louis and Alorton, and the companies of Alcoa and the Alton and Southern Railroad, paying for site remediation. The mound of the former Aluminum Corporation of America ore plant is composed primarily of Red Mud—a byproduct of the extraction of alumina during the refining of bauxite. After further processing, this residue is called ‘Brown Mud.’ Red Mud is a fine grained clay/silt material and has the unique characteristic of being a semi-solid—a material that liquefies and thins when shaken, agitated, or stressed. Geologists and seismologists know this response to perturbation as liquefaction, and is one reason, among many, that this site is such a strange contender for one of the few redevelopment strategies in the area. Alorton partnered with Brightfields Development group to use the process of remediation as site preparation for a 20 MW solar farm development. This brownfield strategy is the first of its kind in the country, and carries the promise to hold a 100 acre solar panel farm—the largest in the Midwest. Construction is hinging on a bill in the state legislature that would require local utilities supplier, Ameren, to purchase electricity from the site for the next 20 years.

The original stockpiling of material took place in the low-lying basin and edges of Pittsburgh Lake—the northerly most lobe of the much larger Grand Marais that arced through the bottoms in this region. In a common practice, industry saw these ‘unproductive’ and undevelopable wetlands as the perfect site for the large-scale storage of waste materials on-site. While current EPA reports note that this site is not hydraulically linked to the adjacent lakes, for anyone with a concern for the underlying ecology of wetlands, this is of course the equivalent of a toxic injection into the bloodstream—with flow gradients and seepage contaminating any waterway in its vicinity. The mound today is a clean dome of imported earth—capping the slag material with 2’ of dirt. A 6’ razor wire fence guards the mound, with neat rip-rap ditches limning its edges.

SAUGET

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds (Untitled XX) Photograph by Jennifer Colten

This colorful heap is composed of the coal combustion waste produced in the former Cahokia power plant just to the south of the mound. With a marbled surface of reds, whites, yellows, and browns, this mound is composed of the fly-ash and other slag produced from burning coal for energy. This mound sits on the river side of the USACE levee—making it subject to inundation. And flood it does. Nearly every year, this mound is worried at by the river’s eddies—dissolving-away its surface and carrying it away downstream. How long, one might ask, until this mound is finally erased by these floods? But while its form may be gradually effaced, its component parts—heavy metals, dioxins, and PAHs—will remain a signal part of the muddy substrata of the river for all time. One of the many contributors to the anthropogenic geological record of the American Bottom.

PULCHER

Significant and Insignifiant Mounds Photograph by Jesse Vogler

What is the threshold for moundness? Such is the question that a researcher of landscape must ask herself. In a topography of subtle ridges and swales, how does a mound enter the field of the legible? The mounds of the Pulcher Site sit along the natural levee adjacent to Fish Lake—a narrow, long slough that runs for a dozen miles across the length of the bottom—as well as along the north edge of the point bar for the Hill Lake meander—the accreted deposits along the inside-bend of a former Mississippi River channel. With its backflow from a rising river, the biota of the lake was regularly refreshed with nutrients and biological life. and here, on the eastern edge of the lake and sited on a local high-point in the point bar known to early settlers as Oklahoma Hill, are a string of remaining mounds. All have been modified by the annual work of agriculture, with the plow regularly working away at their height and redistributing artifacts in the surrounding fields. In certain light, the mounds that make up this site can be read against their agricultural background—with a subtle lift of the ground and its gentle resolution into the furrows.

Owing to its proximity to the main 18th century road through the region—the Chemin du Roi—Pulcher was one of the first sites recognized and identified by French and Americans in the late 18th century. Identified on both the Colott and de Finial maps (definining 18th century cartographic representations of this region) this complex is located at the narrowest segment of the American Bottom. At the southern extreme of what archeologist John Kelly terms the “Cahokian polity,” Pulcher has seen a wave of anglo settlement that built atop and within the mound remains. From Adam Snyder’s “Square Mound Farm” of the 1830s to the present day homes along Oklahoma Hill Road, the landscape setting of the Pulcher group picked up on the high-ground afforded by the point bar in a reading of the bottomland that continues into today’s inhabitation.

-

Crook, A. R. “Origin of Monk’s Mound.”

-

Crook, A. R. “Cahokia or Monks Mound Not of Artificial Origin,” in Science XL:1026. 1922.

-

Squier. Mounds of Mississippi Illustrated

-

Carr, Lucien. The Mounds of the Mississippi Valley, Historically Considered. 1883.

-

Leighton, Morris M. “The Cahokia Mounds: Part II: Some Geological Aspects.” University of Illinois Bulletin” October 28, 1923.

-

Loos, Adolph.

-

Mumford, Lewis. The City in History.