Walking Through Time on St. Philippe

M.J. Morgan

Because a French mining engineer named Philip Renault obtained a large land grant in what would become Monroe County in the American Bottom, we have words to understand a vanished place. Without the notarial records kept by the 18th century French – land sales, labor contracts, wheat, flour, and fur sales, construction plans, sales of horse mills and grist mills, and estate inventories -- we would have few ways of visualizing a remarkable ecosystem just before we lost it. For on the St. Philippe Concession of 1723 lay a great marsh -- Le Grande Marais. Although mentioned over and over in descriptions of property, this marsh is still elusive. The complexity of a mature, healthy prairie wetlands loud with bird and insect voices is but faintly suggested in French notarial language; to us today, the translated legal phrases seem dry and repetitive. A notary tediously copied out records with quill and ink, using the words that no doubt also appear in such records from Montreal and New Orleans: “….such as the whole now lies and stands, which said Louis Honore Tesson declares he well knows, for having seen and visited the same.” 1

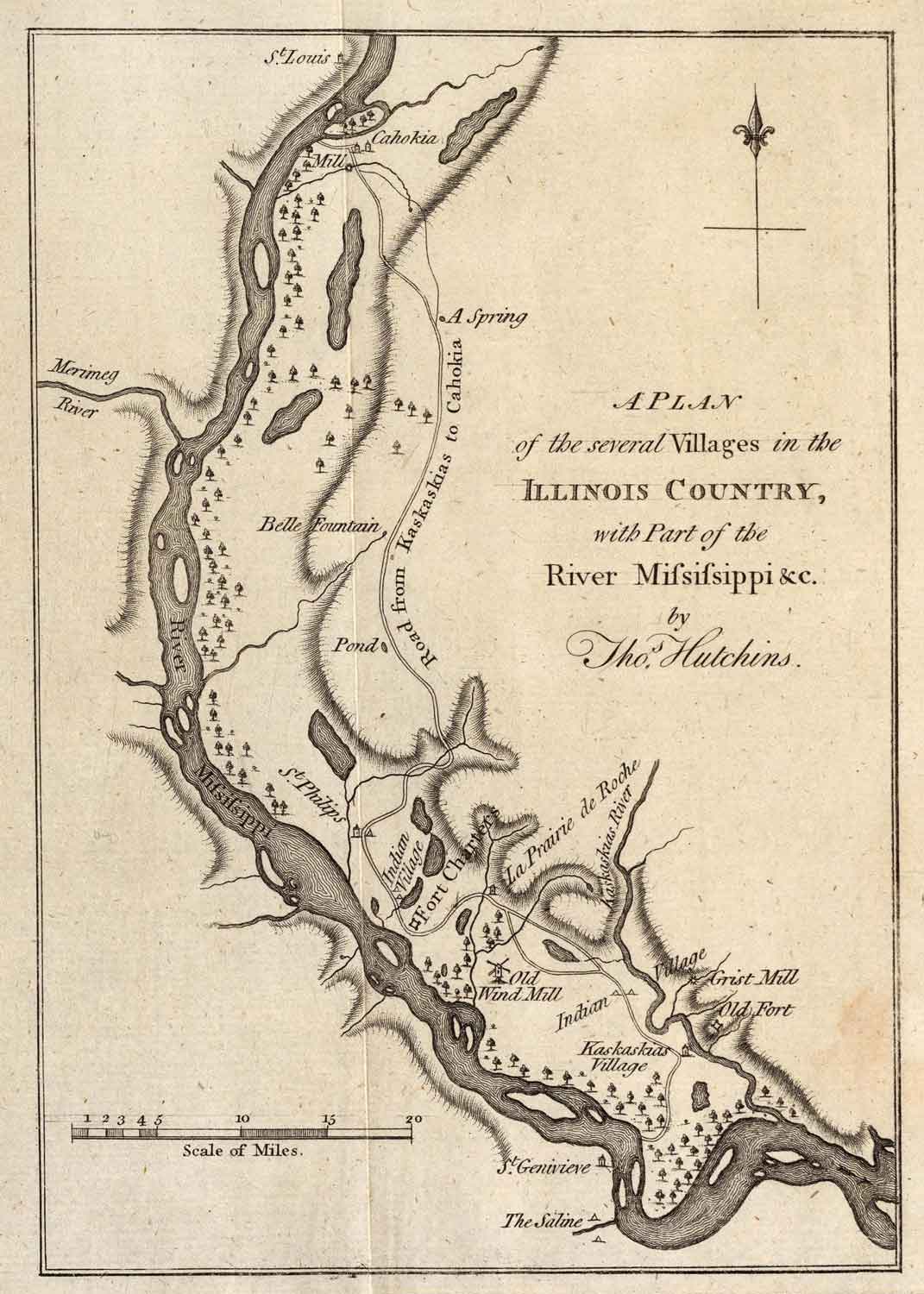

Thomas Hutchins 1778 map of the Illinois Country, showing river, bluffs, floodplain lakes, marshes, forests, villages, and the Chemin du Rois—the Royal Road linking Kaskaskia and Cahokia Villages. “St. Philips” [sic] is shown between the two large lakes in the South (Le Grande Marais)—adjacent to the Indian Village and Fort Chartres.

In the floodplain villages of Prairie du Rocher, Chartres, and St. Philippe, French men and women signed often with an “X,” “not knowing how to write.” But these settlers who went to Fort de Chartres to legalize transactions knew other things: the most intimate details of their physical world, and they left notice for us: the stumps of old cherry trees, where fences and paths lay, a disintegrating house wall, “the first plum tree on the edge of the road,” an ash grove on a hill…or a road leading to the marsh. As they described markers, boundaries, trees, streams, and bluffs to notaries, the natural world on the St. Philippe Concession comes, just now and then, into focus.

“In the year 1726, I, the undersigned Joseph Adam, have agreed with Monsieur Renau, Director-General of Mines in the Province of Illinois, to build for him…a barn in the same fashion as the most beautiful at Kaskaskia…and with the condition that on the side facing the great swamp the crossbeams or posts shall be placed in such a manner that there is the least light possible….” 2

Was the unceasing noise of migrating waterfowl in the marsh a problem? Were humid, hot air and light pouring in from the east concerns for the summer months? This ambitious and beautiful barn was likely the first structure ever built on St. Philippe. Twenty years later, land sale records reveal an interesting landscape mosaic developing west and south of the marsh:

“…one lot of ground…from a cherry tree which lies on a foot path running to the village of the Indians….”3

“…one parcel of land from below the woods to the hills, situate in the “low part” of the prairie Mitchikamia….”4

“…one half of the said concession, consisting in arable land, meadows, woods…” 5

Prairie, meadow, woods. River and coulees, marsh and groves, hills and buttes…the words still summon the land today. These words are the Monroe Bottom.

Monroe Bottoms

Monroe Bottoms. Photo Jesse Vogler

In photographs from November, 2015, a fringe of thickety willows defines a small wetlands, part of the state-owned acreage of Kidd Lake Marsh Natural Area on the St. Philippe Concession. The rust-colored, senesced vegetation that, from a distance, seems to burn in the cold, clear air is unmistakably the insignia of a marsh: it is smartweed, Polygonum hydropiperoides. Growing in dense colonies of stems that burst with tiny, triangular black seeds, smartweed is a critical food for waterfowl, especially ducks. The reddish spread of late-season smartweed across moist land is also a signal that the earth is often inundated. The production of so many seeds is an adaptation; many smartweed plants may die and decompose in a flood, but the species survives through exuberant seed production.

Smartweed defines the edges of a small marshy area where once Le Grande Marais offered both open water and reedy cover for waterfowl. Photo by Tom Morgan, November 22, 2015.

We don’t know what the French landowners on St. Philippe called smartweed, but it is also known as water pepper. The narrow leaves burn peppery-hot on the tongue -- almost too hot at times -- and can be used as seasoning. The French may have gone to the marsh and collected it. They may have used Creole French terms for other dominant plant species of their wetlands: arrow weed, pondweed, and cord grass. They lived on St. Philippe for over forty years, enough time to be born, grow up, and die near an immense marsh; enough time to know well the cacophony of migrating waterfowl, to expect to hear it seasonally. Both French and British observers wrote about the sounds of these birds. In 1751, the Frenchman Bossu said a ‘multitude’ of swans, cranes, geese, ducks, and bustards” had gathered on the Mississippi near the mouth of the St. Francis River. Their noise at night did not cease. In 1765, as French were emptying out of their Illinois villages, leaving their long ribbon farms and shared common land, the arriving British Captain Thomas Stirling described “millions of waterfowl.” 6 These words are powerful in the record: ‘multitude,’ and ‘millions.’

Although this is not always clear on maps of the eighteenth century, the villagers of St. Philippe lived within two miles of a significant wetlands. The map below, drawn by Victor Collot in 1796, shows the little village still lying north of the Fort de Chartres ruins, on the Chemin du Roi (also called the Rue Royal and “the road to the fort”).7

An enlarged portion of the 1796 Collot map, showing old Fort de Chartres and the village of St. Philippe to the northeast. Map of the Country of the Illinois. George Henri Victor Collot; Tardieu. P.F. (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, 1796).

On the Collot map, lying near to the crescent shaped bluffs are two connected, almost cloud-shaped bodies of water. These are likely ponds or lake; they may even be Collot’s depiction of Le Grande Marais. Yet a true marsh has ragged, uneven boundaries that change every year. Across the centuries of pictorial and written representation of this landscape, we have impressions of shapes and sizes; we have word choices like pond, lake, or marsh. But the aliveness and impermanence of these watery places defy easy definition. The stone houses of St. Philippe village clustered within a half mile of the Mississippi; and they shared a sheet of earth, a black-brown alluvium measured off in French arpents, with a complex marshy ecosystem. That earth stretched – and still stretches – straight as a plumb line, to the base of the bluffs two-to-three miles distant. It may have even looked somewhat like this when the French arrived in 1718: “the bottomland would have rolled back from the shore, as much as 50 percent open prairie.” 8

Monroe Bottoms today—with prairie transformed to agriculture. Photo Jennifer Colten.

To find the St. Philippe Concession today, a helpful marker is the old Ivy Landing – or simply Ivy -- area to the southwest of Fults. This long-gone American settlement lay right on the northern surveyed line of St. Philippe.9 If you drive south of Ivy, you are on St. Philippe.

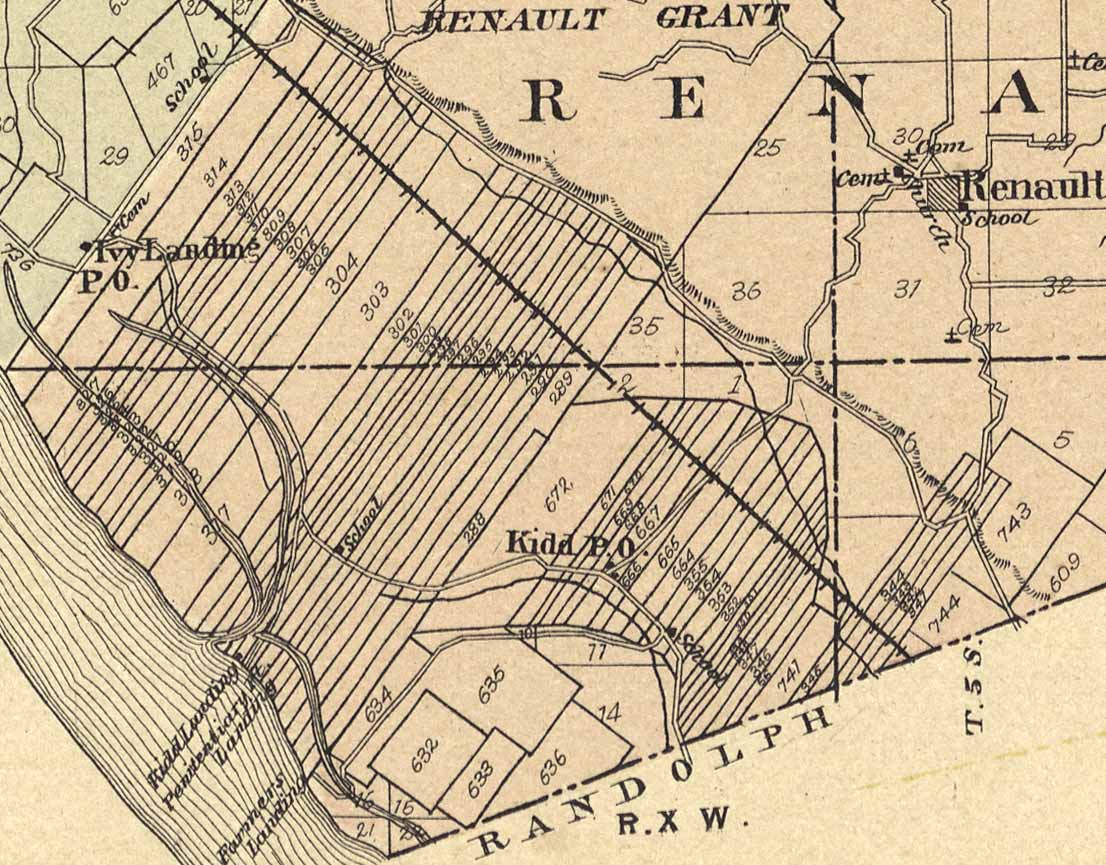

The 1901 Monroe County atlas showing Ivy Landing on the northern edge of the Renault Grant (St. Philippe). The lakes and marshes of the concession are not depicted on this map. Standard Atlas of Monroe County, Illinois (Chicago: Geo A. Ogle & Company, 1901).

The Concession also has its own natural overlook. If you climb to the top of Fults Hill Prairie Nature Preserve, you will ascend wooden stairs so steep, in places they seem more like a ladder.

Fults Hill Prairie

Up and up, straight up the flank of a formidable limestone cliff – and then suddenly, in turning to your right -- you will see it. Le Grande Marais is still there – Kidd Lake and Marsh -- held in a basin of old river channel. It lies below the towering outcropping of Fults Hill Prairie in rectangular sheets of water that, especially at sunset on a winter’s day, suggest enormous mirrors.

Kidd Lake Marsh seen through red cedar branches, high above the floodplain. Fults Hill Prairie Nature Preserve at sunset, November 22, 2015. Photo by Tom Morgan.

The austere, geometric shape of today’s marsh is artificial, defined initially by American farmers who based their land claims on the first rectilinear surveys. The marsh no longer stretches and meanders, some years so full of water it attracted birds as diverse as sandhill cranes, rails, and snow geese. But imagine the brimming marsh and lakes of the American Bottom when the French lived here. Away in the distance, closer to the Mississippi, lay the village of St. Philippe: a hamlet of perhaps sixteen houses, a few streets, and a chapel.10 In the 1740s, the villagers’ world was local and vulnerable. The brief church records for St. Philippe suggest epidemics, deaths in childbirth, and high infant mortality. In early March, 1746, Father Gagnon, the missionary priest from St. Anne’s at Fort de Chartres, rode out to St. Philippe to baptize twin male infants. They were born to “a red slave, a Fox woman, belonging to Chauvin. The father was a Frenchman, Jean Baptiste Loise.” The little boys were named Michael and Louis, but one of them died eight days later, “depart[ing] this life at the prairie of St. Philyppe.”11 Baptisms and burials, marriages and births -- these events marked the rhythm of life here. People lived close to the earth in an essentially pedestrian world. They raised swine, poultry, black cattle, and horses. Life on the floodplain demanded adaptations, such as the use of rot-resistant woods like red mulberry and black oak, the careful placement of stone foundations, post-on-sill construction to avoid ground decay, and as a constant anodyne…the production of brandy and beer. From St. Philippe, in fact, comes a record of a family brewery!

If you lived in St. Philippe, you walked often on old Indian paths leading southwest across the Indian (Metchigamea) Prairie to Fort de Chartres, or you rode a horse farther yet to Prairie du Rocher and Kaskaskia. The Chemin du Roi curved right in front of St. Philippe on its way to the bluff pass. Near to the village to the north ran a coulee, a feeder stream into the Mississippi. In your home lot and yard, you planted fruit trees, apple and cherry, and defined your property with many yards of pickets -- upright stake fencing. We can reconstruct what the little village looked like from notarial descriptions and references: a domestic, social, agrarian world. But it was also a watery world. Le Grande Marais was always there. Its marshy vegetation appears consistently in local names.

“Therefore he comes to ask you be pleased to grant him fifteen arpents of land…the depth from the Mississippi to the hills, situate in the prairie des apacois, bounding on one side the first brook which is in the said prairie, and on the others on the lands not yet conceded on the other side of said brook, and you shall do well.”12

The French likely appropriated the Illinois Indian word apacoya – reported by Pierre Deliette in 1678 as meaning the reeds used to cover Indian homes. French called these marshy prairies filled with stands of cattails and bulrushes “apacois,” both on the uplands and here near the northern boundary of the St. Philippe Concession.13 The “first brook in the said prairie” is probably today’s Fults Creek. Wetlands and creeks defined the cognitive map in the minds of the St. Philippe French; and today, managed wetlands and old creek channels continue to define this place. Their early words – rigolet, coulee, prairie, and marais -- denote a landscape yet visible. Across 275 years stretches a perceptual continuum, a heritage from “the antient settlers of that river.” 14

American place names like Sandy Meadows north of St. Philippe suggest soil conditions; and earliest names for bodies of water and prairies are also messages. At one time, Moredock Lake was known as Eagle Lake, and before that, in French, lac de l’aigle – as it lay near to a bluff outcropping particularly high and formidable. Here bald eagles perched to hunt, scanning the earth below; they may have nested on the cliffs themselves, finding isolated outcroppings of limestone to secure their enormous stick nests.15 By 1800, this haunt of eagles was referred to locally simply as “the Rock.” 16 Over two hundred years later, eagles still skim and wheel over the Bottoms, and, catching updrafts of warmer air, kettle higher and higher.

Of the five French villages on the floodplain, St. Philippe (both village and concession) has the least recorded history. Yet, peculiarly, it is also the place with the most names. How many different ways did the French refer to it! In the notarial records it was the Renault Grant, St. Philippe, Mr. Renault’s grant, Mr. Renaut’s, Concession of the Mines, the prairie of St. Philippe, St. Philippe du Grand Marais, Fort St. Philippe, Saint Philippe, Concession of St. Philippe, and le petit village, the little village. The concession itself lay both on the floodplain and on top of the bluffs, described as running one full league along the river and two leagues to the bluffs; up on the tableland lay more land granted to Renault, as clearly shown in this 1876 atlas drawing of southern Monroe County.

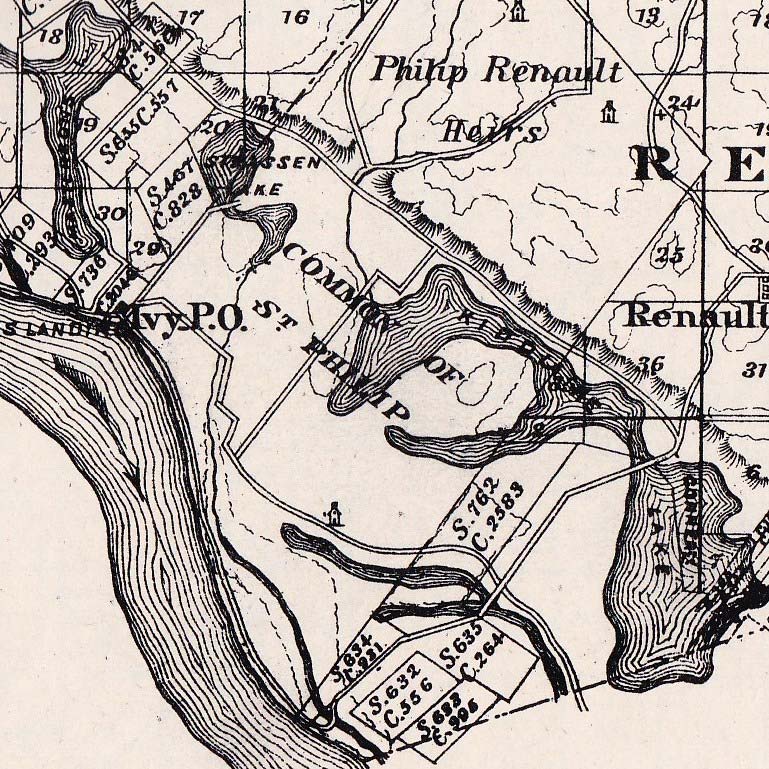

The Renault grant (St. Philippe) lay on both the tableland and the bottomlands. In 1876, the upland grant still belonged to Renault family heirs. Atlas of the State of Illinois and Illustrations (Chicago: Union Atlas Company, 1876).

In the bottomlands, rich alluvium deposited by river flooding over eons yielded French wheat and flour famous in New Orleans markets. The soil was supremely fertile and well-watered. Across the prairie of St. Philippe ran at least two full-flowing streams which the French called the coulees, from their verb couler, to flow. Close to the center of the grant rose a wide swathe of higher ground less likely to have been inundated each spring. Here, family-owned wheat farms were flourishing as early as 1736.17 Later, in the 1750s, a partnership farm occupied some 16 arpents in the middle of the grant. One historian has termed these farms a small “agri-business” in wheat, so successful were they.18 In 1752, perhaps as many as 28 African slaves worked on the Buchet-Bienvenu farm, spread out in the golden wheat fields at harvest time, swinging the scythes and sickles so often named in estate inventories.19

And yet…the concession of St. Philippe remained curiously undeveloped. A study of the old grant in the Monroe Bottom found that it had “never been as heavily settled” as French grants in Randolph and St. Clair Counties.20 Early information about American settlers, recorded in 1788, spoke of them forming small clusters “in the intermediate space between the village of St. Philippe and the boundaries of the Cahokia Grant.”21 Once described partially by the French as the “unconceded land of the King’s domain,” this wet, lake-dotted stretch developed a poor reputation for fever and ague (malaria), often called marsh malaise.22 These descriptors span 100 years of European settlement, and they are revealing: “unsettled,” “an intermediate space,” “unconceded.” The great marsh was holding its own.

A few early Americans settled on St. Philippe in the 1780s, and more settlers did eventually build up early neighborhood communities near Maeystown and Fountain Creeks in northern Monroe County.23 But the impression still holds: St. Philippe grant did not thrive. The French abandoned the little village and their farms at the end of the Seven Years War (1765). Although American settlers began arriving after 1778, the main thrust of settlement was on the uplands, in communities named Bellefontaine, Grand Ruisseau, and New Design.24 Because of this pattern – avoiding the floodplain – we must look to another source for information about the Concession of St. Philippe as it appeared over time. Surveys dot the centuries at interval, with the first occurring on March 24, 1736, when Philip Renault began conveying allotments on his concession to French farmers.25 Nearly one hundred years later, another survey was underway.

A GLO Surveyor on the American Bottom

The day after New Year’s, 1827, a surveyor with the General Land Office, one William Greenup of Kaskaskia, stood on the left (eastern) bank of the Mississippi River near the ruins of old Fort de Chartres. He was looking for a cornerstone once placed by an earlier surveyor. He didn’t find it and recorded, “supposed it to have fallen into the river.”26 He kept searching for old markers along the river, a stretch he described as “very much overgrown,” mentioning large ash, cottonwood, and chinquapin oak trees. He chained across a long pond and then entered timber on the other side. The next day, January 3, he surveyed a line of the Fort Chartres Common Field, planting a marker stone at the ‘Coulee Denaud’ (also appearing as Coulee Denau and Naut). This little stream is so often mentioned in eighteenth century French records that it had to have been one of those collective boundaries, a point of orientation for the people who lived in Prairie du Rocher, Chartres, and the little village of St. Philippe.

From the Coulee Denaud, the surveyor chained his way across a small prairie, walked out upon a frozen lake, drove a marker stone through the ice, and forged on. As he neared the towering bluffs enclosing the old French settlements, he began writing a terse set of notes. These words lie on the page of his notebook in phrases of faded ink, verbs and objects that march vertically down the pages, dashed quickly off next to the survey numbers:

Left the lake and entered the prairie

Left the prairie and entered the lake

Left the lake and entered the timbered land

A few lines later, after recording that the bare, wind-stripped trees on top of the bluffs were black gum and hickory, he re-entered the lake.

Over the next few weeks, we can continue to trace his progress north along the foot of the bluffs, which he estimated at 200 feet high in places.

Looking north along the route of William Greenup in 1827, surveying the bluff line in Randolph County. The setting sun in November, 2015, catches the warmth of the natural limestone here. Photo by Thomas Morgan, Nov. 22, 2015.

William Greenup was being paid to survey the land south of St. Philippe Concession. Eventually, he paused at the intersection of a line he had identified and re-surveyed – the southern boundary of the St. Philippe Common Fields. This intersection, a corner formed with Claim 672 of the Chartres grant, pins the surveyor in time and place. It was now January 17, 1827, and he stood for a moment, writing notes, probably stamping his feet and arms against the cold. Originally, this strip of land running from the river to the bluffs had been known as the Indian Prairie, a dividing referent between the St. Philippe Concession and the fort. Here the bluff thrusts out into space with a truly distinctive shape. Photographs against a wintry sky in 2015 may only suggest what the surveyor had noted, as limestone and earth wear and re-form…but the French likely called this horn-shaped outcropping, “The Butte of the Cherakis” (Cherokees). It shows up in notarial records as the bluff marking the eastern end of the Indian Prairie; and perhaps for many owning farms in St. Philippe, it was also a natural marker for their neighborhood.

The surveyor continued to work in the lands adjacent to St. Philippe. Yet from his field notes, we can learn about St. Philippe as well, for land and water formations flowed into each other across the Bottoms. William Greenup recorded broken bluffs, a lake, land “unfit for cultivation;” he left the lake and entered the prairie, only to soon re-enter a giant frozen arm of the lake. When he had measured the old Chartres Common Fields, he estimated the lake to be six feet deep. In other places, however, the lake that he followed like a river across the floodplain, he recorded as only three feet deep.

It was a very cold January, and the watery land of the old French lands was frozen solid. But the three foot lake the surveyor noted was not known to the former French residents as a lake. Across the approximately forty years of notarial records from the villages of Chartres and St. Philippe, the cumbersome, wordy, legal French is unequivocal: the surveyor’s “lake” is always “marais,” and in St. Philippe, it was Le Grand Marais (the southern-curving arm is sometimes called Le Grande Coulee). In this part of the Bottoms, human traces -- the insignia of the 18th century French, Indian, and African peoples who lived on the grants -- are not dramatic. Archaeological excavations near the fort, the village of Chartres, and in Prairie du Rocher have yielded a rich trove of especially, domestic artifacts. The stone houses there are finally telling their stories.27 But for St. Philippe, we have no excavations, no artifacts. In the end, if we want to know this particularly elusive place, we must use other ways. The people themselves left almost nothing.

And yet… stories still circulate through the Bottoms about what may have been the last evidence of the little village. A current landowner today recounts how his grandfather told him that as a little boy, he knew of two brothers once owning some land near the river, in an especially pretty little meadow near the southwestern corner of the Concession. These brothers had a barn, and the barn sat on a stone foundation that looked as if it had been scavenged from somewhere else. “You can see on the old maps that St. Philip’s lay just to the north of where that barn was. The village was washed away, but of course the stone foundations didn’t wash out. My grandfather and other people thought those barn stones probably came from what was left of St. Philip’s.” 28 This knowledge has survived for so long! St. Philippe was likely destroyed by the Mississippi floods of the 1880s which also destroyed Old Kaskaskia. 29

Photo Jennifer Colten

For St. Philippe, the history is in old maps, a few pages of notarial and survey records… and in stories. But sometimes the stories connect to observations made centuries ago. “St. Philippe is a small village on a very fine meadow,” wrote Captain Philip Pittman in 1766.30 The fine meadows and pretty fields lay in the southwestern part of the Concession. And what was of little interest to observers long ago – the extensive wetlands near the bluffs, the land “unfit for cultivation,” – now draws us. We have learned to see it as part of a miraculous whole, a riverine habitat nearly unparalleled for biotic complexity. In St. Philippe, the lives of villagers played out between the Mississippi River and Le Grande Marais, between two distinct and dynamic ecosystems.31 The river created and continued to sustain the marsh; the Mississippi as it once was can be defined as a “high-energy” river, constantly depositing and scouring. Today, scientists worldwide have unique understanding of rivers, marshes, and freshwater ecology: “A river is more than its main channel,” says a leading riverine ecologist. “The whole floodplain acts as one single organism.” 32 Surveys impose a system of demarcation and ownership, a means of understanding the migration and occupancy of thousands of people over time. It takes historical imagination to view a place like St. Philippe in two ways at once. It is a place imprinted with surveyed ownership lines, French and American…and at the same time, it is uniquely itself, uniquely, marais.

A Sense of Awe: Le Grande Marais

The great marsh that once defined the eastern half of St. Philippe Concession has not disappeared. It is preserved in Monroe County, in a much smaller area, by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. By 2014, the IDNR had succeeded in acquiring 538 acres of the original lake bed, although this acreage lies in pieces and is not contiguous. The original lake was beautifully curving and oddly-shaped; it once lay in a shallow basin of nearly 800 acres, fed by a vibrant and down-rushing Fults Creek. This creek must have been a full and noticeable one yet in 1875 when a lithographic atlas artist drew it and Kidd Lake. His unlabeled Fults Creek runs like an umbilicus into the side of a wondrously-multi-level lake.

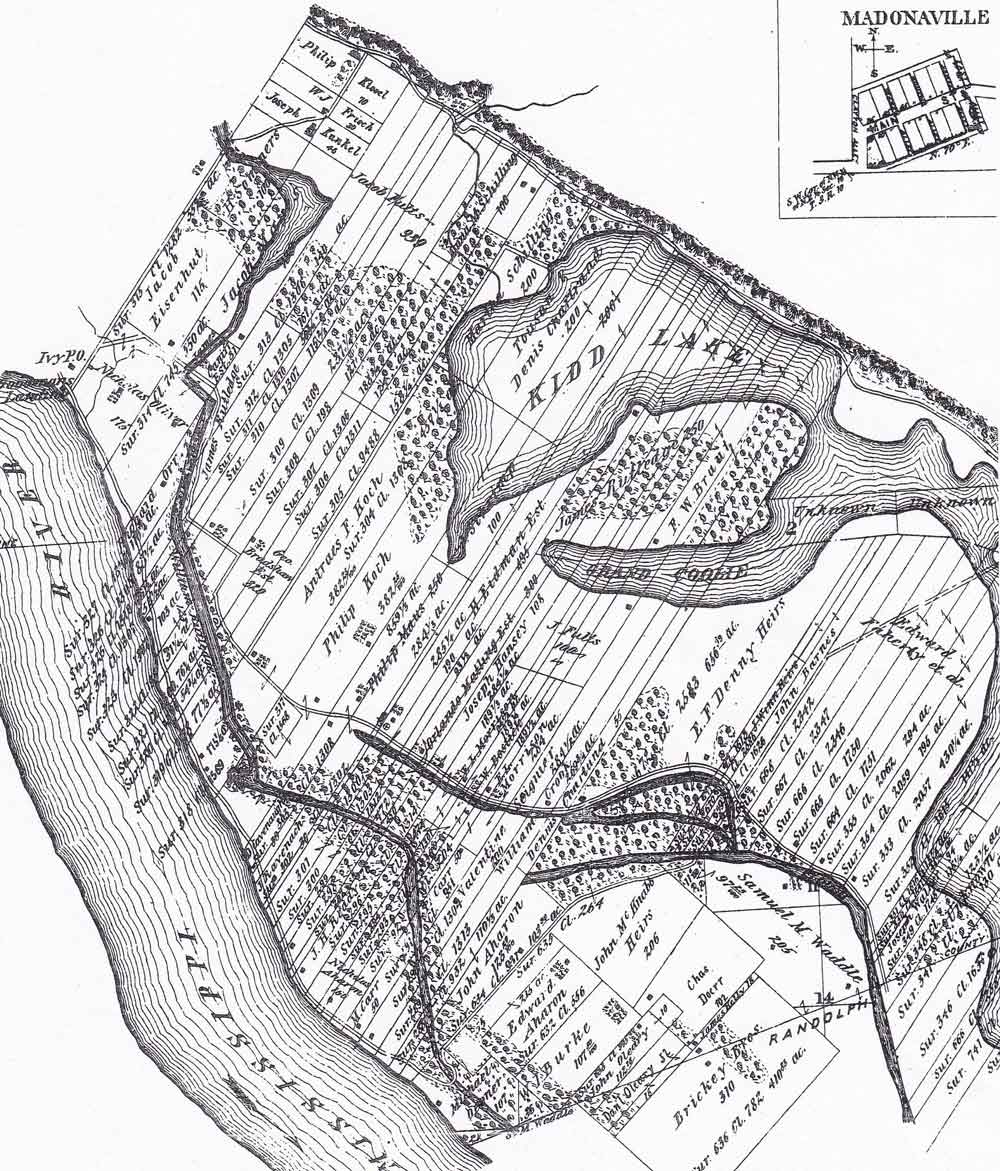

A portion of southern Monroe County as drawn by a lithographer (Brink, 1875). See Combined Atlases of Monroe County Illinois: 1875, 1901, 1916 (Evansville, Indiana: Unigraphic, Inc., 1978). Copy at Morrison-Talbott Library in Waterloo, Illinois.

Although today, the creeks that carved passes through the formidable bluffs are dry or only seasonally active, we can still locate the insignia of Fults Creek. Just north of the Hill Prairie Nature Preserve, a deep cut in the bluffs suggests an ancient torrent of water tumbling from the tableland above, wearing down the limestone, falling into a waiting basin.33 Historical accounts, such as that of British traveler Gilbert Imlay in the 1790s, connect bursting waterfalls to dramatic rainstorms sweeping over the uplands. Imlay described bluffs cut by “deep cavities” through which gushed many small rivulets. On the St. Philippe Concession, many of those small rivulets sent their waters into the great marsh. 34

Well over 275 years later, local people born and raised in the Monroe Bottoms can yet recite the names of streams that, in wet years and rainy months, still trickle down through the limestone. The names are enduring American language referents, brought in by migrants from Virginia and Kentucky: Trout Creek in Trout Hollow and Salt Bluff above Valmeyer; Duck Creek and Fountain Creek once tumbled down several miles north of Moredock Lake, with Fountain Creek leaving the bluffs “at what we call Fountain Gap.” Then look south to Potato Hill, a high, rounded bluff. On the other side of Potato Hill are the stream beds of White Rock Creek, Monroe City Creek, Maeystown Creek and Fults Creek, once known as the creek in Brown’s Hollow. Then comes another push-out of limestone -- Sutterville Hill. Kidd Lake defines the bottomland here, and beyond it, two small creeks wind down from Lake Mildred on the uplands. In the Bottoms are Moredock Lake, Kidd Lake, and once, Conner Lake. These lakes are shallow basins, lying like random thumbprints along the base of the bluffs.35 We sometimes find them described in early American atlases as “periodical marshes.”

All marshes begin as earthen basins. The powerful movement of glaciers and rivers creates them. But how does a muddy basin, scoured out by a catastrophic Mississippi River flood eons ago, become a marsh? It is not a given outcome; the basin must hold water long enough to invite in semiaquatic plants, the smartweeds and arrow weeds, the cattails, soft and hard-stem bulrushes, sedges, reeds, and cord grass, as well as “floating-leaf plants” whose long, slender, pliant stems connect surface leaves with submerged tubers. The yellow water lily, the French macoupin, is the best-known of these. Plant life cycles must be protected with enough water so that they germinate, partially emerge into the still sunlight, and then die naturally, reseeding or sending out rhizomes. Water in basins without plant life, with no organic matter decaying and sealing the black earth, will drain away. Stormy run-off from the uplands and river inundation will seep down and down through layers of river alluvium and leave only odorous mud to dry and crack. 36

Plants make the marsh.

Over millennia, semi-aquatic plants created the Great Marsh of St. Philippe. We know the vegetation was living and dying, decaying and matting, in great, seasonal cycles, for in 1838, we have a description. William Greenup, the same surveyor who had walked the old French Concessions in 1827, had become president of a lottery board. Local residents were seeking to revive the old 1819 lottery approved by the Illinois State Legislature: “for the purpose of draining the lakes and ponds in the American Bottoms.” William Greenup, who had no doubt seen the marshes at most times of the year, wrote a memorial to Congress, stating, “The water of these small ponds and lakes becomes more or less saturated with matter. When they dry up in summer and autumn, the miasma formed and exhaled into the air by a warm sunshine floats with its infecting effluvia and becomes highly noxious.”37

The matter once thought to create malarial infection, the matter that saturated the lakes, was a mass of diverse plants. They could indeed choke the life from pond water. But in the vibrant, healthy marshes of pre-settlement days, the vegetation was under control. A marsh’s life was – and is -- a process both of building up and tearing out. The depth of a marsh depends on changes occurring annually; river flooding and stream run-off bring in sediments, but the bed of the marsh is also impacted by animal life. Down in the marsh bed and up the black, sloping sides, excavations were ongoing: crayfish and some fish species dug into the mud, creating new openings. Vegetation removal was accomplished by waterfowl and mammals who dove for roots and tubers. Beaver and, especially, muskrats, often ripped out large mouthfuls of submerged plant matter, dragging it up onto the shore before eating.38 Diving ducks such as widgeons and mallards, part of those “millions” of waterfowl recorded in the 18th century, also tore out trailing stems and leaves. They looked for open water rippling over an aquatic bed filled with rooted plants -- their choice habitat. Even humans were part of this process. Some early observations of Indian women harvesting underwater tubers describe them wading out into marshes. They felt around in the soft, soupy marsh bottom for tubers and then used their toes to pull out the entire plant.39

The changing of the marshes began when the French arrived. As wheat filled the long, narrow farms and cattle grazed the common lands right up the marsh edge, fur-bearing mammals and Indian women rarely visited Le Grande Marais. The fur trade cleaned out beaver and muskrat, and waterfowl were hunted and consumed. More aggressive American settlers arrived in force, after the War of 1812. They ditched and changed stream channels on their land, and water no longer flowed into the marshes in the same way. After the Civil War, flood-protection levees appeared to keep back the Mississippi overflows that had scoured out sediment and brought in high-nutrient deposits. Then, in the 1880s, the drainage campaigns began in earnest. By 1921, there were six drainage districts in Monroe County reclaiming and draining 52,300 acres of land. Significantly, the district inclusive of the St. Philippe Concession, Moredock and Ivy Landing No. 1, was draining the highest number of acres: 16,700. There were two enormous levees in place one-half mile to one mile from the Mississippi River. 40

Levee top—with the floodable, river-side to the left, and the ‘protected’, agricultural land to the right. Photo Jesse Vogler

All of these human processes, beginning with the first French mattocks chopping up the prairie loam, inaugurated a loss of connectivity. Specialists say, “habitat fragmentation,” or “loss of habitat.” Animal and plant species can no longer move easily across the earth, using water channels sometimes tinier than we can easily see, swimming, skimming, hopping, floating away… as a cattail seed drifts in a rivulet. The Great Marsh of St. Philippe originally flowed out in several directions and softly ended in a wet prairie that sank away into an ancient lake; in turn, the lake opened into a series of small ponds. Even droplets on the earth created connectivity. We visualize this through surveyor entries from contiguous lands to the south, from the Chartres prairies:

“left the prairie and entered the lake”

“left the lake and entered the timber”

“left the timber and entered a long pond”

Studies in the last ten years have gathered striking data about the extent of wetland loss and fragmentation in Illinois. A single set of estimated numbers tells the story of the destruction of migratory pathways for organisms as diverse as crayfish, tadpoles, may fly larvae, or coot chicks. In 2005, researchers working on wetland loss in Champaign County, Illinois estimated that spatial patterns and distribution of wetlands have changed so much that travel and movement options for marsh organisms are almost gone. In pre-settlement Illinois wetlands, an organism adapted to a landscape of connected and watery corridors had “a >50% probability of reaching another wetland within 260 meters [approximately 858 feet]: today that same species faces a 7.8% probability at that distance.”41 Without the ability to find a fresh water pool for food sources, breeding partners, nesting materials, egg-laying, and protective cover, marsh life forms wither. A marsh thrives not in isolation; neither does it self-maintain. The life forms in it migrate; there is flux and flow, activity unceasing but often, unseen. Native Americans in pre-contact days understood this. One wetlands specialist has concluded that Indians knew “there was much to be gained from extending the area of ponds, lakes, and wetlands.”42

In 2016 we too know there is much to be gained; we want back our great marshes. In fact, we recognize the irreplaceable value of even the smallest, patchiest wetland.43 We marvel at the species abundance and diversity a marsh creates. And through many studies of hydric soils, a truth has arisen: the wetlands of the American Bottom, when allowed to absorb seasonal overflow, were the best controller of catastrophic flooding, such as the 1993 flood that wiped out so many small farms in the Monroe Bottoms.44 Wetlands, not levees and channelization, are consummate protectors of life. Even twenty years ago, river scientists were calling for a return of the floodplain wetlands.45 Stated goals now exist for re-establishing pre-settlement conditions at Kidd Lake Marsh Natural Area.46 It seems almost a dream, to re-create that long-vanished world of St. Philippe du Grande Marais. But there are still small, vital signs of a marsh. In the spring when rainfall returns and some streams fill and flow, and cattails green up along the edges of the few remaining, isolated wetlands, the old concession again hosts a memorable bird.

Sightings of the rare common moorhen, Gallinula chlorapus, have been documented for the Monroe Bottoms, specifically for “the wetlands south of Fults.”47 Described as an occasional migrant and summer resident in southern Illinois, the moorhen is now listed as endangered here, where once, it thrived in the St. Philippe wetlands. Most of the French who lived near the great marsh were illiterate; so we don’t know what birds they saw often, knew well, named, or even hunted. In southern colonial Louisiana, a moorhen was known as poule d’eau – water hen, suggesting they were eaten. Surely in the forty years French families lived on St. Philippe, as they walked or rode on the Chemin du Roi passing by the marsh, they saw a moorhen. Even a century later, marsh birds in Illinois were documented in high numbers. The ubiquitous coots were described in 1895 as “far from rare in any marshy situation.” And so the moorhen – known then as the red-billed mud-hen – arrived to the marshes regularly the last of April or the first of May. Ornithologists noted that a moorhen was “an abundant summer resident everywhere in marshes and...prairie sloughs.”48

If you saw one in motion, you might pause in your journey. Nimble and sure, the moorhen balances on large, splayed, four-toed feet, with one especially long hind toe.49 They may seem to walk across the water as they progress on the floating pads of water lilies. In healthy marshes, where open water breaks out in sometimes large areas, water lilies may spread to completely cover the surface. This keeps the water temperature down, which in turn prevents algae growth. The water beneath the carpet of green pads is cooler, clearer.

In June of 1726, all across the Great Marsh of St. Philippe, yellow water lily blooms were gently opening. The winds blew fresh and moist. Moorhens thronged among cattails and bulrushes; they swam out to small willow islands; yea, they ran from lily to lily.

-

See Record K-324 (H459), in Margaret Kimball Brown and Lawrie Cena Dean, The Village of Chartres in Colonial Illinois, 1720 – 1765, Part Two (New Orleans: Polyanthos, 1977).

-

Record K-404, Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part Two.

-

Record K-157, Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part Two.

-

Record K-136, Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part Two.

-

Record K-182 (H1026), Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part Two.

-

M.J. Morgan, Land of Big Rivers: French and Indian Illinois, 1699 – 1778 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010), 64.

-

See discussion of this road and its relation to the village of Chartres and Fort de Chartres in Robert F. Mazrim, At Home in the Illinois Country: French Colonial Domestic Site Archaeology in the Midwest 1730 – 1800, Studies in Archaeology No. 9 (Urbana, Illinois: Illinois State Archaeological Survey, 2011), 16.

-

Morgan, Land of Big Rivers, 70.

-

Standard atlas of Monroe County, Illinois: including a plat book of the villages, cities, and townships of the county, map of the state, United States and world….(Chicago: Geo. A Ogle & Co., 1901); see also United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey, Renault Quadrangle, Illinois-Monroe County, 7.5-Minute Series (Topographic), 1993.

-

This description of the village appears in the account of Captain Philip Pittman, The Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi, originally, 1766 (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1906). See also, “The Village of St Philippe,” in “History and Development Along the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail,” researched by Dennis R. Patton, revised June, 2014. Copy at the Morrison-Talbott Library in Waterloo, Illinois.

-

See Records D-108 and D-110, Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part One.

-

Record K-139 (H60), Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres, Part One.

-

Morgan, Land of Big Rivers, 15.

-

This phrasing in “Report of Committee of Congress, June 20, 1788,” in Kaskaskia Records, Virginia Series, Volume II, Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library, Volume V, ed. by Clarence Wadsworth Alvord (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1909), 479.

-

David Sibley points out that bald eagles will nest on cliffs as well as in tall, sturdy trees. See David Allen Sibley, The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 219.

-

“ Fults, Township 4 South, Range 10 West, Survey 314, Claim 745, Monroe County, Illinois, FEMA Mitigation Flood of 1993, Fults,” in Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey (Springfield, Illinois: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, 1977), 8, and endnote 19. Copy at Morrison-Talbott Library in Waterloo, Illinois.

-

See the La Croix family discussed in Carl J. Ekberg, French Roots in the Illinois Country: the Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 217.

-

Ekberg, 218; for enslaved Indian and African peoples in French Illinois, see also Carl J. Ekberg, Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

-

For discussion of the Buchet and Bienvenu partnership on St. Philippe, see Ekberg, French Roots, 167.

-

“FEMA Mitigation Flood of 1993, Fults,” Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey, 7.

-

“Memorial by Barthelemi Tardiveau, February 28, 1788,” Kaskaskia Records, 464.

-

See G. Koehler, M.D., “Lottery Established in 1819 by the State of Illinois to Raise Funds for Improving the Public Health by Draining the Ponds in the American Bottoms,” Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 35, 1928. By 1819, autumnal malaria was well-established, and “fever and ague” deterred settlement. However, malaria parasites were not originally part of the marsh environment of the Bottoms. They were brought in by European settlers. Malaria is described as being “highly prevalent” in southern France throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; but its climax period in America has been pinpointed as 1850-1899. See Ernest Carroll Faust, “The History of Malaria in the United States,” American Scientist, 39(1) (January 1951), 121-122.

-

For the American settlers on St. Philippe, the Drurys and McNabbs, see Margaret Kimball Brown, History as they Lived It: a Social History of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois (Tucson, Arizona: The Patrice Press, 2005), 184. See also the list of American families in Patton, “History and Development Along the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail,” 169.

-

“FEMA Mitigation Flood of 1993, Fults,” Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey, 6, 7.

-

Patton, “History and Development Along The Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail,” 169; see also Ekberg, French Roots in the Illinois Country, 43.

-

Find this entry and the others which follow in “Illinois Land Records, Original Illinois Field Notes, Books 453 and 462,” Microfilm I333.08, ILLI 2, #39-55, copy 2, Illinois State Library, Springfield, Illinois. I am indebted to Rita Stephens and other reference librarians for their invaluable assistance in pinpointing the Chartres Concession field notes.

-

For the best and most current archaeological overview, see Robert F. Mazrim, At Home in the Illinois Country: French Colonial Domestic Site Archaeology in the Midwest 1730 – 1800 (2011).

-

Anonymous communication to author, Monroe County, Illinois, November 22, 2015.

-

One local history states this happened in the late 1880s; other sources pinpoint the flood of 1881 in which the Mississippi leapt inland, into a new channel beyond the little village. See Brown, History as They Lived It, 258; for channel changes in the Mississippi, see “Geomorphology Study of the Middle Mississippi River” by Edward J. Brauer, David R. Busse, Mr. Claude Strause, Robert D. Davinroy, David C. Gordon, Jasen L. Brown, Jared E. Myers, Aron M. Rhoads, Dawn Lamm, U.S Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District Engineering Division, Hydrologic and Hydraulics Branch Applied River Engineering Center, Foot of Arsenal Street, St. Louis, Mo, 63118. Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District and Mississippi River Stakeholders, December 2005.

-

Reported in Patton, “History and Development Along the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail,” 169.

-

This description of the village appears in the account of Captain Philip Pittman, The Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi, originally, 1766 (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1906). See also, Patton, “The Village of St Philippe,” in “History and Development Along the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail.”

-

Kirill Kuzishchin of Moscow State University, cited in David Quammen, “Where the Salmon Rule,” National Geographic, August, 2009, 40.

-

See Appendix D, “Site History,” in Kidd Lake Marsh State Natural Area Levee Repair and Protection Conservation Plan for the Incidental Taking of Threatened and Endangered Species (Springfield: Illinois Department of Natural Resources, 2014).

-

Morgan, Land of Big Rivers, 13; see also Gilbert Imlay, A Topographical Description of the Western Territory of North America, 3rd ed. (London: J. Debrett, 1797).

-

Informal interview with Valmeyer resident Rick Roever, November 22, 2015. See also “FEMA Mitigation Flood of 1993, Fults,” Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey, 7, 11.

-

For good overviews of marsh-making processes see Milton W. Weller, Freshwater Marshes: Ecology and Management, 3rd edition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), especially Chapter Two, and J.G. Gosselink and R.E. Turner, “The Role of Hydrology in Freshwater Wetland Ecosystems,” in Freshwater Wetlands: Ecological Processes and Management Potential, ed. by Ralph E. Good, Dennis F. Whigham, and Robert L. Simpson (New York: Academic Press, 1978).

-

William Greenup, cited in Koehler, “Lottery Authorized in the State of Illinois,” 196; see William Greenup’s description, 197.

-

Weller, 9; see also “Resource Uses” and “The Marsh Edge,” especially, in Freshwater Marshes, 31, 33; William R. Clark, “Ecology of Muskrats in Prairie Wetlands, “ in Prairie Wetland Ecology: the Contribution of the Marsh Ecology Research Program, edit. by Henry R. Murkin, Arnold G. van der Valk, and William R. Clark (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 2000).

-

See “American widgeon,” Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute at Urbana-Champaign, online at http://wwx,inhs.illinois.edu/collections/birds/ilbirds/3/ Last accessed December 7, 2015.

-

G.W. Pickels and F. B. Leonard, Jr., “Engineering and Legal Aspects of Land Drainage in Illinois,” State of Illinois Department of Registration and Education, Division of the State Geological Survey, Bulletin No. 42 (Urbana, Illinois: State of Illinois, 1921), 28, 40. For a good overview of the tile drainage movement in Illinois, see M.B. Bogue, “The Swamp Land Act and Wetland Utilization in Illinois, 1850-1890,” Agricultural History Vol. 25, 1951, and J.E. Herget, “Taming the Environment: the drainage district in Illinois,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 71, 1978.

-

Lisa M. McCauley and David G. Jenkins, “GIS-Based estimates of former and current depressional wetlands in an agricultural landscape,” Ecological Applications, Vol. 15(4), August, 2005; see abstract for quoted material.

-

Hugh Prince, Wetlands of the American Midwest: A Historical Geography of Changing Attitudes (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997), 83.

-

R. D. Semlitsch and J.R. Bodie conclude that “small wetlands are extremely valuable for maintaining biodiversity.” See Semlitsch and Bodie, “Are small, isolated wetlands expendable?” Conservation Biology 12, 1998.

-

Morgan, Land of Big Rivers, 102.

-

See, for instance, Richard E. Sparks, “Need for Ecosystem Management of Large Rivers and Their Floodplains,” Bioscience, Vol. 45(3), Ecology of Large Rivers (March, 1995).

-

See Kidd Lake Marsh State Natural Area Levee Repair and Protection Conservation Plan for the Incidental Taking of Threatened and Endangered Species (Springfield: Illinois Department of Natural Resources, 2014).