Sediment Worlds: Soil and Agriculture in the American Bottom

Gayle Fritz & Angela Miller

This itinerary is written from the perspective of the American Bottom’s most defining material quality: its soil. One of the elements linking the archaeological history of the region to its present-day patterns of land use is the rich history of agricultural practices in the Bottom. But what does it mean to write a cultural history of place through soil? To bring the landscapes, technologies, and values of ancient and contemporary farming practices into conversation? These are some of the questions that this itinerary of sediment and sentiment looks to address.

Soil Cross Section

Greater Cahokia—including the largest urban center ever built north of Mesoamerica before European contact and today a UNESCO World Heritage site—refers to the entire American Bottom floodplain and the upland hinterlands on both sides of the Mississippi River during the time between A.D. 1050 and 1350. During this time, tens of thousands of people were drawn to this region for trade, ceremonial events, and social activities—with a parallel emphasis in the cultivation of the crops. Today the remains of this ancient cultural region are overlain by highways and by a patchwork of marginal businesses, extractive industries, and large- and smaller-scale farming. While little is known about many of the archaeological sites that surround Cahokia Mounds proper, this entire region can be understood as a constellation of settlement and cultivation extending well beyond the boundaries of State Historic Site.1 Each time the plow or rain heaves up the earth, artifacts from centuries ago—stone and ceramic—as well as more recent fragments—metal, glass, and pottery implements from the 18th century forward—return to view. The soil of the American Bottom bears the material traces of the long history of occupation and settlement.

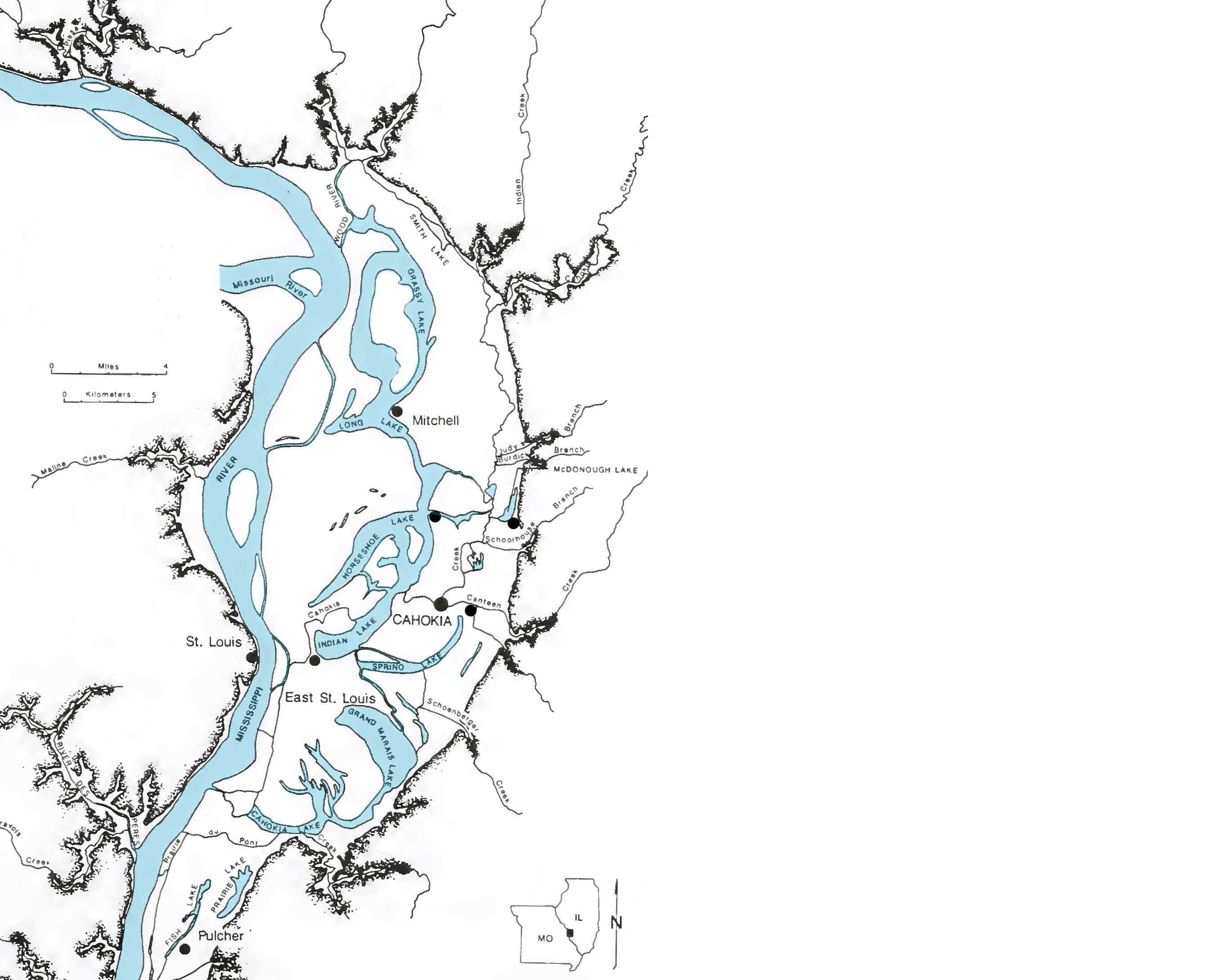

American Bottom Map circa 1800

Topographically and hydrologically, the Mississippi River Valley gathered together the tributary waters of rivers that connected the East Coast—the Ohio and Tennessee—to the trans-Mississippian West—the Missouri River—in a vast regional system with its own natural cycles and processes. It was that very cycle of flooding and deposition that has made the region what it has been for millennia—a culturally and historically complex region of human settlement.

Across the epochal shifts in occupation—from pre-Conquest to European and Euro-American settlement to contemporary industrial farming—certain determining environmental patterns persist, allowing us to track and compare variations in the ways different cultures have responded—productively and less so—to these conditions over time. For at least two thousand years, people living here decided where to build their houses, where to plant crops, and where to construct sacred precincts based on characteristics such as elevation, drainage (or lack of it), and soil properties. These causal factors are easier to read today in the realm of settlement and farming than in the intangible arena of native myth and cosmology.

EUROPEAN PLANTING PRACTICES

Yet early European settlers often found the natural cycle of flood and deposition as running counter to the agriculture and land use requirements of settlement. For those who moved into the American Bottom beginning in the 18th century, this cycle remained a continual challenge to settlement—evidenced by the numerous village erasures and abandonments during the period of French colonization. Nonetheless, through the long period of colonization as evident in the river valleys of Quebec, the French developed a pattern of land division that was partially attuned to the dynamics of the floodplain.

French settlement in the American Bottom followed a tripartite system of land use that remains a material lesson in transitional land use patterns. Structured around a survey practice that divided land in narrow, parallel strips running perpendicular to a primary watercourse, the arpent survey system was principally a way to provide a similar cross section of soil types and geographic conditions to each plot. The American Bottom formed a clear geographical terminus for these parallel bands, with most arpents stretching from the river to the bluff. Developing around this survey armature, a tripartite division of village, common fields, and commons was organized in a specific territorial vision of social relations. Adjacent to the core nucleus of a village, each family received a strip of land for individual cultivation, with the entire assemblage of strips known as the common fields and enclosed with a fence. Further distant from the village was the commons—a collective territory for the grazing of livestock and the gathering of firewood.2 As a unified system, French land use practices occupy a distinct place between ecological specificity and systemic generality. In recognizing a watercourse as the primary organizational system for settlement, there is an initial ‘reading’ of place based on natural topographic and geographic conditions. From there, the striation of the arpent system both acknowledges the shared soil conditions adjacent to waterways while simultaneously dividing this soil continuity into discrete parcels of production. Coupled with a practice of rotating fields and a legal framework for collective ownership, French settlement marks a distinct transitional system between Native practices and Anglo-American systemization.

Anglo-American settlement patterns imposed hegemonic grids on a natural topography—gridded property boundaries, gridded agricultural fields, gridded roads, gridded towns and cities—and extended this latticework across the continent in the unbending uniformity that air travel has made visible. This infrastructural uniformity ignored local conditions as the grid was overlain on land that varied greatly in its drainage patterns, the character of its soil, its relationship to uplands and declivities sloping toward the river systems. Looking at the tilled and rigidly bounded fields of today, we are reminded of older planting practices --an organic, seasonally and geographically adjusted pattern of food production that minimized the risks of climate events by exploiting topographical variations.

Then and now, fertile soil was arguably the most valuable natural resource for people living in this region. But today such fertility is severely challenged by industrial agricultural practices and by the very interventions meant to control the natural cycles of flooding that have defined the region in its challenges and its possibilities. Throughout the American Bottom, the channeling of water to prevent flooding has meant that the periodic depositing of rich topsoil in the agricultural zones can no longer occur. The soil over decades of flood control has become diminished, nutrient deficient, requiring fertilization by farmers. Such fertilizers then penetrate into the ground water, or wash back into the Mississippi as part of the seasonal cycle, carried down to the river delta at the terminus of the Mississippi where these accumulations of nitrogen cause great algae blooms that starve local biodiversity, the very biodiversity upon which surrounding communities depend.

Most of this large floodplain zone today is agricultural land where modern farmers grow corn, soybeans, wheat, horseradish, and, to a lesser extent, garden produce, in gridded and ploughed acreage. To make this regular pattern possible meant various forms of large-scale intervention in the landscape: new diversionary canals and drainage ditches, levees, and ceramic field tiles buried beneath and between the fields. Farming in the American Bottom today depends on these interventions to manage, although not without a cost, the natural flooding of the Mississippi and streams such as Cahokia Creek and Schoolhouse Branch, which flow into it from the uplands to the east.

NATIVE PLANTING PRACTICES

Seeing the topography of the American Bottom from a pre-Conquest perspective, then, is to read the land in very different ways: it is to read ridges and swales and swells, ancient channels and meander scars, uplands and bottomlands, toe-slopes and fans, all shaped by the cycles of flooding, deposition, and erosion that characterize floodplains. The Mississippian agriculturalists of the centuries before European arrival used topographical variations to their advantage. Loess-covered uplands and lower wetlands: each ground condition pointed to specific seasonal planting patterns that used good drainage or—in seasons of drought—benefitted from flatter topography where rainfall was retained by the soils for a longer period of time. This then was a temporal as well as spatial adjustment to conditions at any given place and time.

Native American farmers of centuries past had to pay close attention to slight variations in elevation signaling soil and moisture differences. Past mosaics of fields and Native villages formed complex, sinewy patterns starkly unlike those of today’s rectilinear, monocropped grids. Native farmers minimized the impact of weather events with planting patterns that distributed risks throughout fields with different soil and topography. Extreme weather cycles meant that some fields would do better than others, depending on level of incline, water retention, or flooding patterns. Some would drown and rot in saturation; others would wither, but some would always survive within this pattern of variation. If we could travel back in time, we would immediately recognize the ancient landscape as the foundation for an agricultural economy that flourished in the face of an unpredictable nature.

The Sponemann site, located less than 3 miles northeast of Cahokia Mounds, is an archaeological settlement that was built and occupied by families who may have been among the most affluent and influential members of Cahokian society outside the central precinct marked by Monks Mound and the more than 100 other earthworks within and adjacent to the modern State Historic site boundaries. Here, a unique clustering of farming strategies, domestic lifeways, and ritual practices can be read through the archeological record of the soil. Pre-Conquest habitation at this site spans several centuries, with two time phases having special interest for the purposes of this itinerary.3 The earlier of these phases consisted of small houses and surrounding features built during the last two centuries of the first millennium A.D., a time period called the Emergent Mississippian because it immediately preceded the “big bang” of explosive population growth at Cahokia. The second period of special interest to us is known as the Stirling phase (A.D. 1100-1200), a century that witnessed Cahokia’s highest level of cultural complexity. At this point, Sponemann consisted of a typical Mississippian hamlet at its north end, with a southern zone devoted to a ritual precinct in which ceremonial gatherings were held and esoteric paraphernalia and knowledge were displayed.

Farming strategies changed in one important way during these centuries: before A.D. 900, little if any corn was grown in the American Bottom region. Instead, the earlier suite of crops included mostly native plants that were domesticated thousands of years earlier in the North American heartland. The sunflower is the best known of this pre-maize Eastern Agricultural Complex, but other members include: a relative of quinoa that we call goosefoot; a relative of sunflower known as marshelder or sumpweed; two grasses with seeds that ripen in June, weeks to months before the seeds of other crops mature; a buckwheat relative called erect knotweed; and a type of squash that was domesticated in eastern North America independently of the Mexican-bred pumpkin. In addition to these plants, whose ancestors were all native to the American Midwest, farmers in this region and beyond grew bottle gourds and tobacco.

A CROSS SECTION OF SEDIMENT (SOIL)

Traveling today from the bluffs to Sponemann, Cahokia, and beyond, one can still read the differentiated topography that shaped the locally varied planting patterns of pre-Conquest Mississippians. People who lived here from at least A.D. 400 until A.D. 1400 or later relied heavily on crops grown in fields extending along the fertile terraces of Schoolhouse Branch Creek and the toe-slopes at the base of the bluff line to the east. The Schoolhouse Trail, maintained by Madison County Transit, today offers cyclists and hikers an excellent view of woods, fields, and modern wetland environments in the American Bottom. Following the trail as it cuts down from higher ground east of North Bluff Road (U.S. Highway 157) beside Schoolhouse Branch creek, anyone can see the dramatic difference between the loess-covered uplands to the east and the vast expanses of alluvial bottomlands that stretch westward to the Mississippi River.4 What is not so easy to see are the subtle ridges and swales left by long-ago meanderings of abandoned river channels.5

In a paradox of contemporary archeological funding and practices, the Sponemann site was excavated during mitigation prior to construction of Interstate 255—a project that would ultimately erase forever the archeological traces in its path. Highways have taken their toll on both cultural and natural resources, and destroyed evidence of older patterns of movement and settlement in the landscape, but such modern interventions have also offered opportunities for excavations sponsored by federal transportation projects such as construction of I-255, contributing a wealth of information about ancient communities that preceded Cahokia and flourished during its heyday, A.D. 1050-1350. While federally-funded archaeological mitigation carried out by crews from the University of Illinois yielded a great deal of information about this and related sites along the I-255 corridor, even these scientific excavations are inherently destructive—and archaeologists can never return to those features in the right-of-way of Interstate 255.

Interstate 255 crosses the Sponemann site north of its intersection with I-55/70 and immediately south of Horseshoe Lake Road. Hikers and cyclists on the Schoolhouse Trail can look south across the Schoolhouse Creek’s channelized bed and onto the farm fields of the undestroyed, western edge of Sponemann, just west of the I-255 overpass. It takes a keen eye to notice how the higher ground occupied by the site dips down to the old meander scar that borders Sponemann’s west edge; most uninitiated visitors to the area miss these signs because we’ve mostly lost sight of the history that gives them meaning, both geological and cultural. Prehistoric houses and pit features still lie buried beneath the plowzone of the western part of the Sponemann site, where fields planted today are rotated between corn and soybeans. Reading the landscape is an act of historical recovery.

Development does not always bring knowledge. A horseradish field north of I-64 formerly planted by Carl Weissert—a longtime resident of the American Bottom—was once full of Late Archaic artifacts; but like many other farm fields, this property was sold to commercial developers early in the 21st millennium. Several businesses and parking lots now cover that soil, terminating the potential for future farming or archeological research. Nevertheless, even today large stretches of the bottomland in Metro East remain agricultural, contributing far more farmland than economists in the early twentieth century predicted would survive after industrial, commercial, or residential development. As Carl Weissert told a group of students visiting from Washington University in St. Louis in April, 2016: “We [farmers in the Metro East] can’t believe we’re still here.” Going deep into the richly sedimented landscapes of the American Bottom—a palimpsest of ancient and contemporary worlds—might just perhaps save us from the cultural shallows. But only through concerted preservation.

ENVIRONMENTAL NARRATIVES OF CAHOKIA

Our collective narratives about the past often reflect our unexamined assumptions and anxieties in the present. Public memory is a collage of contemporary experience; fragmentary knowledge of the past; wishful projection; and fear. Even the relatively more “objective” fields of scientific research and archaeology are filtered—perhaps clouded—by errant elements from contemporary experience and history.

Numerous dioramas at the Cahokia Visitors’ Center animate the Mississippian past of the American Bottom for present-day visitors. One of the largest and most lovingly realized is an idyllic panorama of family life and activities in the Mississippian heartland: peaceful indigenes pursue their non-invasive activities of basket-making, harvesting, and hunting, fishing, and cooking in an edenic landscape of wetlands dotted with groves of useful fruit-bearing trees, deep clear rivers brimming with large catfish and bullheads, bordered by sloping uplands.

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Park Visitors Center. Photographs by Jesse Vogler

<

>

In this idealized prospect, however, one notices that the uplands are furrowed by deep gullies eroded by rainwater, leaving the hills stripped and denuded-- odd symptoms of environmental crisis in a setting otherwise defined by a harmonious balance of human and natural. This feature of environmental degradation represents one side of a contested vision of Cahokian society being debated by archaeologists in the present. There are those who believe that Mississippian cultures had so deforested their surroundings—as wood was needed to build increasingly complex structures—that no root system remained to hold topsoil in place, washing it away and leaving an eroded landscape. On the other side are those who resist this narrative of how local Native Americans altered their natural environment, contributing to the eventual decline of Mississippian culture in the 1300s. Were these gullies part of the landscape of Cahokian nature/culture, or an invention of those who would visit the ecological crises of the modern era onto the past?

Other contested versions of the past define the archaeological debates of the present. The contemporary archaeological preoccupation with corn as the central defining crop of Mississippian culture seems filtered through the patterns of present day monocrop agriculture, as well as by a belief in the priority of Mesoamerican cultures spreading their material cultures and their agriculture north from its centers in central Mexico. Corn, which was domesticated in Mexico, did make its way northward to the U.S. Southwest and from there eastward across the Great Plains. But it was not embraced as a staple food until shortly before A.D. 1000. The archaeological record in the American Bottom area shows clearly that corn was added to the existing Eastern Agricultural Complex rather than replacing the indigenous cultigens.6 By the Stirling phase occupation at Sponemann and other early Mississippian villages in this area, refuse middens and storage pits were filled with the residues of a diverse mix of available crops. Wild plant foods and, of course, fish and game animals, continued to be harvested and hunted in order to feed the hungry residents of Greater Cahokia. Corn was only one of a rich variety of local food sources.

THE EARTH MOTHERS OF THE AMERICAN BOTTOM

Present-day popular conceptions of Cahokia also embody persistent ideas about the gendered distribution of power, ideas filtered through two centuries or so of visual representation. Dramatic images of “ruling elites” or “paramount chiefs” feature men atop mounds decked out in imported finery, high above the assembled “commoners” in the plaza below. However, from what we know about Native American division of labor across eastern North America, scholars and members of descendant communities have inferred that Cahokia’s farmers—and those who preceded and followed them—were women. Evidence of the central physical and symbolic importance of women in the agricultural world of Mississippian society are the hundreds of fragments of female statuettes carved from Missouri flint clay and interpreted as representing an ancient, supernatural earth mother being. Here is where archaeological evidence counters the historical marginalization of women with images of startling power.

Earth mother images were found in one of the structures situated in the ritual precinct that occupied the southern part of the Stirling phase Sponemann village. Present-day members of the Mandan and Hidatsa—descendants of the Siouan-speaking tribes of the Upper Missouri River—recognize in these Mississippian figurines a mythic being they call the Grandmother or Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies, guardian of the vegetable world that included all life-sustaining crops.7 At planting and harvest times, prayers and offerings were made to this earth mother figure, and esteemed elders and members of female societies performed as priestesses, magically producing kernels of corn from their bodies. Although we don’t know with any precision what kinds of ceremonies took place at Sponemann or other Mississippian sites, they more than likely related to cycles of fertility and renewal. The contributions of women as food producers and mothers probably made them key players in many of these rituals, either publicly or behind the scenes. We should not overlook the knowledge, privileges, and powers unique to women, sanctioning them to select, enhance, and distribute crop seeds and to work in the fields together, generation after generation.

The so-called Birger figurine powerfully recalls the role of women in Mississippian cultures and projects the energies of woman, seed, and earth in the act of planting. A replica of the Figurine sits in a vitrine at the Cahokia Mounds Visitors’ Center, while the actual artifact is curated by the Illinois State Archaeological Survey in Champaign, Illinois. It is currently (2016) on loan to the Saint Louis Art Museum, in the Ancient American Art gallery 113, along with numerous other flint-clay figurines and Mississippian copper plates. The statue was retrieved from the excavated site of BBB Motor, located less than one mile south of Sponemann, and named after the owner of the field, Barney B. Birger, who ran an automotive business in Collinsville.8 The Birger figurine is formed of flint clay, a soft stone found in sinkholes along the Missouri River west of the city of St. Louis.9 Seven inches or so high, the back and top of the figurine’s head was sliced off by heavy highway construction machinery—also during the I-255 construction project—as it dug into the shallow pit where she was buried. But the damage hardly lessens her symbolic force. A woman—breasts exposed—squats on the ground, a massive feline-headed snake curling around her lower legs and feet. She rests her left hand on the snake’s thick body. Her right hand holds a hoe with which she is tilling or stroking the snake’s body. Around her upper chest hangs a strap from which is suspended a flat rectangular carrying bag or basket on her back. Behind her, the snake’s body splits open under the action of hoeing to produce two squash vines, one of which follows the outer perimeter of the base, while the other climbs up the woman’s back to her left shoulder. Six large squash fruits wrap their way up her back, becoming progressively less mature in stages that reveal the cycle of growth and flowering.

MEXICAN CONFLUENCES IN THE AMERICAN BOTTOM

Earth mothers and ancient ones punctuate the multicultural history of the American Bottom, drawing these pasts into the present and endowing the stretches of small shops, convenience stores, trailer parks, strip joints, and lots lined with acres of trucks, with some small measure of grace. Another ancient earth mother—the Virgin of Guadalupe—Nuestra Señora de las Americas— also presides over the entry to a small Mexican grocer on the road to Cahokia.

The shrine to the Virgin is located at the Tienda El Maguey, where the produce section includes ripe papayas and mangoes, along with fresh prickly pear cactus fruits (tunas), leaf pads (nopales) and occasionally the leaves or budding stems of Mexican-grown chenopod plants (epazotes and huauzontles). Surrounded by memorials to lost loved ones, the Virgin brings together several generations of Mexican Americans who call the American Bottom home, permanently or seasonally, in shared admiration for the mother who protects. Her diminuitive scale—like that of the Birger figurine—is deceptive. This Christian earth-mother reaches across centuries to make common cause with others who have symbolized the linkages between soil and air.

The body of the Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies is linked rather directly to the soil; her action of hoeing opens up the earth to make squash. Her kingdom has now become regimentally ploughed fields of soybean and corn, monocrops that dominate the agricultural production of the Bottom today. In between are small stands of local seasonal produce, some of it harvested by the farmworkers who celebrate the vision of the Virgin who appeared to an Aztec man—Juan Diego—shortly after the Conquest to reconcile the native people of Mexico to Christianity. Now she nurtures a sense of attachment to the Mexican homeland still so strongly felt by Mexican-Americans, and she also helps new arrivals feel less exiled from the home they left.

Another element that helps anchor Mexican immigrants to their new home are the edible plants that grow wild throughout North America, consumed by ancient and modern, Mexicans and migrants alike, some of whom come to work on farms like Carl Weissert’s Green Acres Farm. The headquarters for Green Acres lies just south of Interstate 64 on the eastern edge of East St. Louis, Illinois, and can be reached by taking Exit 6 off of I-64. Neighboring businesses include several strip clubs, Big Mama’s BBQ, and the Southwestern Illinois Correctional Center, converted from the former campus of Assumption High School and today surrounded by high fences and topped by a guard tower. Numerous prominent Illinois citizens including Senator Dick Durbin attended this former school. Further east on I-64, just before the Caseyville exit, plowed fields stretch for miles to the north and south, a few miles west of the bluff line.

Weissert grows corn and soybeans in fields cultivated before him by his father and grandfather. Until recently, Weissert also followed in the footsteps of his ancestors by growing horseradish, which has been one of the signature crops of the American Bottom since the late nineteenth century. This region is still recognized as the largest horseradish-producing region in the United States; Collinsville hosts an annual Horseradish Festival in early June featuring live music, crafts, kiddie rides, and food.10 In 2001, Gayle Fritz worked as part of an archaeological team mapping one of Weissert’s horseradish fields—located between the Interstate and Bunkum Road—in search of Mississippian sites that would yield understanding of Cahokia’s agricultural system. Instead, they discovered a site dating much earlier, to the Late Archaic period: 3000-4000 years before present (1,000-2,000 BCE). They found thousands of fragments of chert and sandstone tools littering the surface of an area measuring approximately 26,000 square meters.

Weissert’s horseradish fields were planted by hand with horseradish rootstock by seasonal field workers from Mexico. Weissert recalls that these migrants recognized the artifacts as ancient cutting and grinding tools not unlike those used by their indigenous ancestors in Mesoamerica. Knowing our interest in both wild and domesticated plants, Weissert told a story about stopping to visit with farmworkers planting horseradish, during their lunchtime, and finding they had gathered early summer greens such as purslane and pigweed, which have grown for millennia as common weeds in cleared fields. Edible greens of many species—generically called quelites by Spanish speakers—provide a crucial nutritional component to the diets of traditional farmers across Latin America. Now these transient horseradish planters traveling up from Mexico were folding ancient greens into tortillas as a welcome addition to lunchbox fare. As Carl’s wife Sue noticed, these new arrivals were also more closely tied to indigenous Mexico, and to native language groups, some barely speaking Spanish. Their presence in the American Bottom—where they came into contact with ancient stone tools, and where they collected and consumed plants whose seeds are commonly recovered from archaeological middens across the Midwest—fed a deep historical taproot linking indigenous populations across time and space. They bring us full circle in appreciation of this richly sedimented landscape and the foods it provides.

But let us always return to the soil that nourished the snake whose body breaks open with squash. That soil is also dug up and piled high along the extractive zones that checker the Bottom: great hills of sand and gravelly earth. Monstrous earthdiggers tower over the ground, reaching to the height of the artificial mountains of sand and gravel. The bowels of the earth, the bowels of culture, exposed to the sun once again.

-

Most of these sites are now situated on privately owned farmlands or within industrial zones and residential areas.

-

For more on French settlement patterns and practices, see: Ekberg, Carl. French Roots in the Illinois Country. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

-

Fortier, Andrew C., Thomas O. Maher, and Joyce A. Williams. The Sponemann Site (11-Ms-517): The Emergent Mississippian Sponemann Phase Occupations. FAI-270 Site Reports. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1991. And Jackson, Douglas K., Andrew C. Fortier, and Joyce A. Williams. The Sponemann Site 2: The Mississippian and Oneota Occupations. American Bottom Archaeology: FAI-270 Site Reports. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

-

Loess are deposits consisting of scourings from the pre-Pleistocene era, blown eastward and coating the plains with minerals from the Rockies.

-

Swales are cavities in the landscape formed by water runoff or other natural processes.

-

Simon, Mary L., and Kathryn E. Parker. “Prehistoric Plant Use in the American Bottom: New Thoughts and Interpretations." Southeastern Archaeology 25(2) (2006): 212-257.

-

Bowers, Alfred W. Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organization. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

-

Emerson, Thomas E., and Douglas K. Jackson. The BBB Motor Site. American Bottom Archaeology: FAI-270 Site Reports. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984.

-

Emerson, Thomas E. and Randall E. Hughes. “Figurines: Flint Clay Sourcing, the Ozark Highlands, and Cahokian Acquisition.” American Antiquity 65(1) (2000): 79-101. And Emerson, Thomas E., Randall E. Hughes, Mary R. Hynes, and Sarah U. Wisseman. “The Sourcing and Interpretation of Cahokia-Style Figures in the Trans-Mississippi South and Southeast.” American Antiquity 68(2) (2003): 287-314.

-

Daley, Bill. “Hidden Roots.” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 2005. Accessed June 10, 2016. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2005-04-20/entertainment/0504200309.