The Landscape of Fragments and Memories: Intangible Heritage on the American Bottom

Michael R. Allen

How Are Intangible Places / How Are Places Intangible

This itinerary presents a long tour across historic sites in the American Bottom whose physical forms have changed over time. These sites are not categorically “lost,” or “abandoned,” or “erased,” although those attributes describe some of them. Instead, these are sites whose composure possesses obvious indeterminacy. Hence, the title adopts the cultural resources management term “intangible heritage” as a conceptual anchor. While all of these sites retain elements of infrastructure, altered landscape and architecture, their conditions offer only partial evidence for past forms.

The geographer and artist Trevor Paglen reframes the art critical question “What is art?” into “How is art?” Those who follow this itinerary may also find that rephrasing the questions “What is a site?” into “How is a site?” provides better ontological support to understanding and appreciating these places. A trail of fragments, ghost buildings, ruins and puzzles ought to provoke endless wander, rather than perpetual confusion. However, the person who judges the extant forms of these places against the assumed image of their authentic, full historic appearances will return from this tour dejected. These sites fails to “reproduce the cosmic scheme and correct history,” in the words of J.B. Jackson. Instead they challenge fixed views of geographic and architectural history, and may mean more across time as their physicality becomes more readily “historic.” (The fact that these sites also possess semiotic indeterminacy seems like a strangely congruent historic element, since the first Europeans to settle the American Bottom, the French, were largely illiterate.)

Route 3. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Absence is not a glorious implication, read in broken infrastructure and architecture that serves a mapping function in its remainder. In the American Bottom, the land generally absolves settlers and opportunists of their failures and triumphs with less discrimination than Charon. Across the American Bottom, sites of erasure exemplify what Paolo Virno calls “the memory of potential” – a “not-now” that never was and may never be. Travelling the American Bottom with old maps seeking lost sites, the memory of the lost past becomes the image of an invented future. Can there be a time when these old stories are marked in space as well as time? Can we find what the map shows but the place conceals? If the only manifestation of a history is archival, is “place” even a function of space or linear time? The disparate experiences that the American Bottom contained across its settled time seem to defy human abilities to mark land or recall moment.

The buried succession of the American Bottom leaves a neatly provocative, if not restorable, surface. The end and the beginning of many sites are equally obscure. Eduardo Galeano’s thesis that the Europeans who conquered the Americas never knew where they were and are still discovering that fact seems starkly affirmed across this land. From the tilled fields on Kaskaskia Island burying the dreams of empires, to the empty mausoleum raising a perpetual eulogy to a lost land speculator, to the lost factories of Granite City and East St. Louis, to the continued erosion of St. Louis’ shadow city across the river, to the parking lots and onramps where railroads once deposited New York capital in the form of ties, rails and locomotive steel – the American Bottom is a place where we discover what we have lost, and what we have found to lose. What we see may be the least measure of the historic importance of any place in the American Bottom.

Kaskaskia

David Gendron, the mayor of Kaskaskia, Illinois, told a Chicago Tribune reporter in 2011 that his primary reasons for residing in the state’s former capital cum second smallest town population 14) were being a native and great duck hunting. “I was born and raised here, and that’s why I stay here,” said Gendron. At the time of Gendron’s statement, the town was long past the catastrophic 1881 flood that essentially removed its urban sinew, and somewhat removed from the 100-year Great Flood of 1993 that threw the town under nine feet of water for several days. No reordering forces stronger than those floods can ever visit, creating a sense of calm and ease of life reflected by the mayor’s words.

The land mass of Kaskaskia today is labelled an “island” officially, although its form in the modern era was longest as a peninsula formed by the Mississippi River’s curve, and the merger with the Kaskaskia River. The Illini settled north of the town site, and traded and farmed here possibly for centuries. Europeans settled the land in the eighteenth century, and brought a cycle of settlement and erasure that saw each epoch of Kaskaskia lasting briefly. Illini settlement, by contrast, had been longer and less disruptive.

Kaskaskia, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Somewhere beneath the rich soil of the town lay secreted remnants of a past that included serving as Illinois’ first territorial and then first state capital from 1809 through 1819, providing a strategic location to French Jesuit missionaries led by Father Jacques Gravier arriving in 1703, receiving Louis XV’s gift of a church bell in 1841 and witnessing the birth of John Willis Menard, the first black member of the United States Congress, in 1838. Along the way, floodwaters became intercessional forces of erasure between settlement and denouement. Another force came from the British Army, which nearly levelled the town in 1763. George Rogers Clark, the inland waters’ foremost continental geographic statecraft agent during the Revolutionary War, liberated the town on July 4, 1778. Clark’s symbolic ringing of Louis XV’s bell provided the eponym for its moniker “Liberty Bell of the West.” Prior to that moment, Kaskaskia had been the administrative center for the British province of Quebec.

This little ghost town carries few signs of its role in inland statecraft. Few towns that had carried key administrative and missionary functions for three different nations are manifest today in a form that could be mistaken for an average fallen Midwestern grain elevator or tavern stop. The stately orthogonal street grid betrays a French colonial origin, comparing to the grids of New Biloxi (1711) or New Orleans (1725) downriver, but the smattering of small houses surrounded by dark, fecund fields are indistinguishable from the general regional vernacular architecture. Immaculate Conception Church and its two-story red brick school house, boarded and damaged, provide a clue that a subtractive force worked through the place.

Immaculate Conception Church and Liberty Bell of the West Gazebo. Kaskaskia, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Another clue at Kaskaskian grandeur is the remaining presence of the Liberty Bell of the West, situated as an implied venerated ritual object in a small shrine building. The bell and the signs rupture the generic sense of time and place. Out of the rupture emerges history itself, which makes visitors’ minds into camera obscura for replaying colonial drama. The visitor may being wondering why this segment of the American Bottom is labeled an “Island” on maps, why it sits west of the Mississippi River but has an Illinois telephone area code (and a Missouri ZIP code), and why its lonely inhabitants seem thoroughly nonplussed by its past.

Kaskaskia is emblematic of the object-form of historic erasure on the American Bottom. There are no real marks of compensation for Kaskaskia, no likely speculative futures of economic or touristic power. Kaskaskia, in its commonplace nonrecordant landscape, barely raises its past for inspection. The church bells’ occasional ringing, and the accompanying soft glow of electric light through stained glass windows across wintertime low evening sunsets, are the closest the town has to a spectral architecture. The church seems to anticipate an invisible multitude. Kaskaskia’s streets, however, are not ripe with broken foundations, dead-grass areas atop driveways or any of the lines the explorer follows to map the past. Kaskaskia is the anti- ghost town.

Valmeyer

Today Valmeyer is a hybrid, divided city – with the oldest section in the American Bottom, missing many buildings but retaining a street grid, a park and other vestiges of settlement that survived the 1993 flood. The older section is 400 feet atop the bluff, representing the “new Valmeyer” that was built for some $35 million after the flood. Once this section sported a sign reading “Valmeyer II: A New Beginning,” inscribing the sequential nature of this place. Twenty years later, however, “new” Valmeyer seems settled, and its authenticity no longer questioned. The relationship between the two halves has receded, so that “old” Valmeyer is more like the once-was towns of the American Bottom – places that lost population through changes in human systems, not due to natural attack.

Empty town blocks cultivated in soybeans. Valmeyer, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Yet Valmeyer’s divided corpus offers a strange simultaneity of the vernacular town plan, a grid defined by streets parallel and perpendicular to a rail line, and the contemporary vernacular of the Garden City-derived suburban plan, with curved streets that terminate more often that go through, cul-de-sac endings and open site lines. Old Valmeyer epitomizes the German- American appropriation of the French colonial orthogonal plans, imported from Aquitaine’s bastides and scaled to a wide range of sizes in the new country. New Valmeyer has a taxonomic character far less historic, but no less authentic. The new plan fits the new life of the town – a town of people less dependent on walking, less dependent on a single employer and more likely to travel to Waterloo for a night’s entertainment.

"Rising to New Heights". Valmeyer, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Old Valmeyer, platted in 1909 and named for a Swiss family (in German, “valley of the Meyer”), arose to provide housing for workers at a large stone quarry adjacent to the town. The Iron Mountain Railroad began constructing a rail line to Chester through Valmeyer after 1900. Previously, the only rail route through Monroe County passed diagonally southeast through Waterloo. Construction of the Iron Mountain necessitated ample crushed limestone, and the provident bluff was well-suited. The quarry necessitated massive cuts into the bluff in the room and pillar fashion. Eventually the railroad was built, and the line later sold to the Missouri Pacific.

The quarry passed into the ownership of the Columbia Quarry Company, which maintained operations through 1937. In 1921, the quarry reported extracting 1,000 tons per day. Most of the rock went to agricultural use in the last two decades of operation. Valmeyer thrived as workers built houses along its streets. In the 1930s, with state and federal assistance, a grand Art Deco public school was built replete with zigzag terra cotta ornament. Even after the quarry scaled back, its new life as an indoor mushroom farm (open through 1983) provided employment. When the flood waters first threatened the town in August 1993, Valmeyer was a well-kept, well- loved historic place.

Flooding captured a town that had not yet met its centennial, although this was not the first such instance on the American Bottom. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assessed that 90% of the houses of Valmeyer could not be repaired, along with the school. Buyouts led 600 of the town’s 900 residents into a new planned community, while others scattered or rebuilt to take their chances. The built heritage of Valmeyer manifest in synecdoche such as the bell of St. John Church of Christ, relocated to the new steeple, and the terra cotta frieze of the old school, placed in a wall in front of the new building. Such locational alterity in Valmeyer’s signs of stability was epitomized in then-Mayor Dennis Knobloch’s affixing a handwritten “Office of the Mayor” sign to his truck so that people could find their elected leader.

Rock City Cold Storage and National Archives & Records Administration Annex. Valmeyer, IL. Photos by Jesse Vogler

<

>

While Valmeyer’s hemispheric form offers legible record, the transformation of the quarry offers an intriguing form of preservation – and an irony of state security. The quarry today is called “Rock City,” and its carved interiors house cold and records storage, save for a vacant section that includes intact mining equipment that was used for some time after the quarry was scaled back in 1983. Since 2009, Rock City has been the site of the National Archives and Records Administration’s largest offsite inland depository. The federal government expelled people from the land to limit liability for flood insurance, then turned around and placed pertinent secure documents right in the same town.

The quarry is above yet-reached flood lines, however. Still the landscape of federal power in the American Bottom presents land management regimes – flood control, agricultural subsidy and price control, expulsion of First Americans, provision of postal routes -- that offer unresolved tensions and sites that constitute sites for reflection on citizenship. The “hold outs” of the American Bottom defy time by adhering to older regimes of management, manifest on the land itself, while the residents of new Valmeyer assent to the new regime, off of the land their habitation is attempting to manage.

Harrisonville

Southwest of Valmeyer along Illinois 156, a crossroads marks the site of Monroe County’s first seat of government, Harrisonville. Today, Harrisonville is a geographic term, not an architectural district. The bounds of the landscape are elusive, corresponding to the fact that the town was moved even once before to avoid flooding. (The original site lies under the channel of the Mississippi River.) Out amid the fecund fields of the American Bottom, where few buildings stand today, once many Illinois settlers envisioned economic growth and political self- determination.

Settlers farmed this area as early as 1780, and the original town was approved by the Board of Commissioners of St. Clair County in 1809. Today archaeologists could locate lost landmarks in the vicinity that include Brashear’s Fort, which stood from 1786 through 1795, and the salt wells around the bluff that garnered the name “Salt Lake Point.” (The bluff itself near Valmeyer bears the chilled, gaping intrusions of 20th century limestone quarrying.) Harrisonville itself also could stand to be excavated to trace more of its contours. Written histories offer much, however, especially after Illinois created Monroe County in 1816 and made the town the county seat.

Harrisonville drew its name from General William Henry Harrison, later president, who even owned land (that he may not have visited) north of town near Moredock. The location at the Mississippi River was strategic, although ferry service was not opened until 1826, after the county seat relocated. McKnight & Brady’s general store opened early as an economic hub whose vitality to farmers forged an immediate hinterland for Harrisonville. The ferry eventually expanded trade to Herculaneum in Missouri, which was serving as county seat of Jefferson County in the ferry years. Harrisonville may well have become a major town, had it ever aligned its strategic roles in economic, political and transportation systems. There was no moment when the town was county seat, trade hub and ferry port, although the town came close. Waterloo, the later county seat that today has 9,000 residents was better aligned – and free from the perpetual flooding.

Early aspirations for direct democracy in Illinois were bolstered by a mass meeting at Harrisonville in 1822. Illinois’ state constitution limited the franchise to white males who had reached 21 years of age and had resided in the state for six months, but provided no rule on candidacies for office. In early elections, candidates typically self-nominated through the press. The Harrisonville populists wanted townships and counties to hold nominating meetings, where nominators could not become candidates, and more than one candidate must be nominated. Voters would then be asked to vote only for those candidates nominated. The idea did not take hold immediately, but was influential on the development of partisan politics in the state.

In the same year as the meeting on voting, the United States government passed a law establishing a Post Road from Harrisonville through Columbia and Cahokia to St. Louis. Postal routes in this period established arterial passages not simply of information, but also of government power. At one end of the road, Harrisonville was a transmission point for federal authority, as well as economic activity reliant on banking and debt. Harrisonville’s prominence in nineteenth century Illinois was reliant on its placement in systems of governance, communication and monetary circulation. The function of Harrisonville in these intersecting systems was replaced by other cities, especially Waterloo, which became the Monroe County seat in 1825. Harrisonville reported 25 houses in 1883, but today has fewer than a dozen spread out along the two roads. The flood of 1993 claimed many remaining dwellings, which FEMA demolished after the owners agreed to buyouts.

Miles Mausoleum

Atop Eagle Ciff near the village of Fountain, the Miles Mausoleum seems to offer a stone face peering across the American Bottom toward Missouri. Today, the Mausoleum enjoys a recent partial restoration and lighting project, but for many decades its bluff face showed the intrusions and paint marks of vandals. Miles Mausoleum had an uncanny, nearly sinister presence matched by the tales of trespassers, speculation about its builder and a very real incident in which bodies were removed and burned in effigy on Eagle Cliff. The memorial landscape, which includes the adjacent Eagle Cliff Cemetery, was overgrown with grass and dockweed until the flood of 1993, when it provided a perfect overlook for curiosity-seekers. Every monument needs a public, and Eagle Cliff suddenly had one. After 1993, maintenance resumed, headstones were restored when possible and funds were eventually raised for extensive work to the mausoleum.

Restoration of the hallowed land of the cemetery compensated for the neglect of the resting places of dozens of early Monroe County settlers, ranging from eponymous land barn Stephen W. Miles to Revolutionary War veterans. The work also ratified J.B. Jackson’s assertion of the “necessity for ruins,” or the redemptive function of abandonment of historic sites that allows their restoration to serve the identitarian needs of later generations. Eagle Cliff is now a grant scenic overlook, enshrining Miles’ own boastful statement that he owned every acre within the view; a site for the veneration of an origination myth for Monroe County that places a white man instead of First Americans as an original settler; and a patriotic ground where veterans of a litany of foundational continental wars (Revolutionary, War of 1812, Civil) are interred. All of these functions are rooted in real history, of course, but withhold other histories: federal-sanctioned land speculation and Illinois’ contorted history of sanctioned slavery.

Born to Welsh parents and raised in Cazenovia, New York, Stephen W. Miles served in the War of 1812. Like many veterans, he received a land warrant for a tract in the Northwest Territory, but unlike others, he actually relocated to claim the land. In 1819, Miles arrived on the American Bottom, and quickly embarked upon a profitable and successful speculative land purchase plan. Miles purchased the unclaimed or unwanted warrants of other veterans, and bought other lands, until he held 600 acres of fertile American Bottom farm land. Miles commandeered slave labor to clear his land, situating this Eastern settler in Illinois into the more contorted reaches of American patriotism. Stephen W. Miles’ reliance on slavery was hardly atypical for an ambitious Southern Illinois farmer and landowner, however.

At the time that Miles settled on the American Bottom, Illinois was rife with a contradictory constitution that forbade slavery but allowed five types of human bondage. Matthew Stanley describes the state as a “society with slaves” instead of a “slave society” – a state seemingly folded into a Northern way of life but retaining a clandestine dependence on Southern oppression. The tolerance of slavery actually had roots in the French colonial code noir or “black laws” of 1720, which opened Illinois to slavery. Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 outlawed slavery in the territory, it did not regulate leased slaves or indentured servants. The American Bottom was the arena for human bondage ahead of Miles. Phillippe Francois Renault brought leased slaves to work mines near present-day Renault in the late seventeenth century.

The permissiveness of slavery was debated in Illinois toward Miles’ death in 1859, with passage of the exclusion law in 1853 preceding the Lincoln/Douglas debates in 1858. Illinois saw an emerging consensus that was against the last vestiges of slavery in the state, but nonetheless hostile toward black citizenship. Miles’ own relationship to the enterprise of slavery at his death is unknown, but he did retain indentured servants. Miles would bury an indentured servant in his great mausoleum, and bequeath part of his estate to another in his will.

Ahead of his death, starting in 1858, Miles commissioned a grant mausoleum in the bluff at Eagle Cliff. The structure was designed in the manner of a Greek temple, and built of marble quarried in Italy. The architectural image of the Green Revival had proliferated across the nation after the 1830s, and presented an implied lineage between a young, experimental nation and a tradition of ancient democratic civilization. By the Civil War, the Greek Revival fell from fashion, as the nation’s certainty about its own identity cleaved violently into pieces. Miles’ monument remains one of the finest and most elaborate nineteenth century buildings in Monroe County. Its connotation of an indelible national identity is not truly at odds with its builder’s aspirations toward capitalist empire or willingness to enslave others. In fact, these bundled anxieties about citizenship, individualism and the uses of the frontier make it a definitively American marker. With Miles’ own house near Fountain wrecked in 1982, and descendants scattered across the country, the mausoleum is the last place inscribing Miles’ name and work in the area. Still that name is strongly placed, and the view from Eagle Cliff not greatly changed since Miles’ own death.

Ft. Piggott

Indeterminacy in the landscape of the American Bottom produced moments of great scenic awe, as well as evidence that confounds the object-seeker and the all-knower alike. The fields of the American Bottom along the bluffline west of Waterloo and Columbia are punctured by decadent vestiges of farmsteads, with vernacular frame structures like corncribs, barns and chicken coops increasingly absent. On roads including Bluff Road, Levee Road and B Road, there are scenic markers of agricultural heritage.

The road pattern in this section, and the presence of farm settlement, illustrate that the road patterns here respond to land ownership established prior to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. While the Public Land Survey System’s Township and Range system was effectively implemented in Monroe County, it worked around cadastral patterning that relied on topographic, watershed and ownership lines. Thus the American Bottom in Monroe County presents the image of lace, with intersecting curved lines that have more in common with the colonial metes and bounds systems than with much of the rest of the Midwest. The Cahokia- Kaskaskia Trail, a Peoria tribal route now incorporated into Bluff Road today, provided an early nonlinear aspect to the land. Thus the American Bottom here is deeply historical, with land patterns retaining a rustic character that preserves First American infrastructural intervention.

An early settlement near Columbia was Piggott’s Fort, erected by Captain James Piggott in 1783 just at the foot of the bluff one mile and a half from where Columbia would be platted. Piggott’s Fort, later known as Fort Piggott, was the first American settlement in the American territory. At the site, a small creek named by French settlers as Grand Ruisseau flowed through the land, providing potable water. At the fort, Piggott (who had served under George Washington in the Continental Army) gathered 14 families within a group of inward-facing buildings that fortified the encampment. For the next twelve years, Piggott and others lived on the site, during which time Piggott started a Mississippi River Ferry. Eventually the fort was wrecked, and the creek renamed by white settlers as Carr Creek.

Today, the exact location of Fort Piggott remains uncertain. The foundation of a leveled barn, built of coursed native rubble stone, stands along Bluff Road across from Sackman Field, a small airport. Since historians dated lumber used in the barn construction to the 1700s, locals have held that the barn foundation was part of Fort Piggott for at least the last 25 years. The need for determinacy that seems endemic to American art-historical approaches to cultural heritage seems to have led to the need to have an object marking the fort, even in the absence of more than conjecture. Conjecture plus object may be the equation of historic preservation in the United States.

Yet lately Columbia locals have reopened the prospect that the barn foundation is a separate remnant (notable in its own right, as farm heritage in the American Bottom is also significantly vanishing). In 2011, Columbia even hosted Find Piggott’s Fort Day, and a construction company owner and copper dowsing rod expert named Dylane Doerr pronounced afterward that the site of the fort was actually located where the air strip and a cabbage field are now located. Dwayne Scheid, archaeologist with the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, followed with an excavation. The results were inconclusive. Perhaps the question of location is not where the fort may be, but how the fort may be found. The locational uncertainty already has the collateral benefit of preserving the barn foundation, which may otherwise have been lost. The conservation of the object may not always be the conservation of the object. Yet heritage may still be preserved, with full ambiguity.

Waterloo Railroad Piers

East of Water Street in Cahokia, on each side of the canal, stand six concrete piers as cryptic and prosaic as the parts of Stonehenge. These piers once supported the railroad bridge over the canal built by the East St. Louis, Columbia and Waterloo Railroad. Known more popularly as “The Waterloo Railroad,” this route served as an interurban passenger line from downtown East St. Louis to downtown Waterloo between 1906 and 1932. Freight service utilized the route between 1920 and 1937 after oil was discovered around Cahokia, and the line provided a route to Socony-Vacuum’s refinery and tank farm in East St. Louis. Today little of the route exists, although its track-free right-of-way still runs through Cahokia and Sauget. A car repair house still stands outside of Waterloo, Illinois as well. Infrastructural fragments are locational markers, and explain relationships now ciphered, such as the link between the forested, vacant Socony- Vaccum site and the oil wells around Cahokia and Dupo.

The Bell and Pontiac's Murder

Much of Cahokia today consists of a 20th century vernacular landscape, one that belies its early French colonial urbanism based on a typical orthogonal grid. Cahokia sprawls across mostly flat land, with ranch houses, parking lots and retail buildings dodging occasional creeks, channels and green spaces. Camp Jackson Road remains the central commercial thoroughfare, with its roadscapes fully linear and fully in the mode of retail strip. Nothing in the built environment divulges that Cahokia in fact is Illinois’ oldest town.

Among the big boxes, gas stations and strip malls of the road stands a small studio and art space called “The Bell.” Presented by Bortolami Gallery and organized by Los Angeles-based artist Eric Wesley, The Bell is one of the American Bottom’s oddest adaptive reuses. The Bell also conjures a morass of conflicting American modes of cultural identification. This Mission Revival structure, built in 1980, invokes traditions of Mexican food, Spanish colonialism and white American fast food culture – in the middle of a town founded by French colonists and named for a Mississippian settlement.

That the Taco Bell, a sturdy building rendered in concrete block made as brick and clay tile, opens into the confusion of European settlement of North America is clear. The symbolic mundane, however, is also apparent. Taco Bell is a ubiquitous signifier, and without a clever reuse such as an art gallery, almost signifies nothing in roadside America. Of course, the original Taco Bell in Downey, California, built on 1962 and the architectural prototype upon which the three-arch and belfry-carrying Cahokia building is based, became the subject of an intense historic preservation campaign last year. The image of the Taco Bell of 1962 was legible cultural heritage – so too may the 1980 building, as it embodies the chain’s early expansion. (Ironically, the first restaurant closed around the time that the Cahokia branch opened.)

Somewhere to the east of The Bell, the great American warrior Chief Pontiac met his demise. There is no tension to note between the two sites, except for the anxiety that quietly obscure, taken-for-granted generic American landscapes may induce. Something is always silent that would shatter the calm. The geographic locus of Pontiac’s demise is not specific, but its enunciation speaks to the racial strife that continues to define North American partitioning. Pontiac died in Cahokia because the French of the town, founded after the establishment of a mission in 1696, recognized First Americans as equals. Yet the circumstances of Pontiac’s death invoke hostility between the British and native tribes that foreshadowed later American tribal expulsion. Cahokia stands as a site of rare continental consilience between First Americans and Europeans.

Pontiac had risen to chief of the Ottawa by 1755 and later chief of the Council of Three Tribes, consisting of the Ottawa, Potawotami and Ojibwa. Pontiac led a campaign to expel the British from tribal lands, while providing support to French settlement. In 1763, Pontiac led a successful series of battles against the British around Fort Detroit, but never captured the fort itself. As Pontiac retreated to the Illinois territory, the French ended up shifting political alliances to the British in 1764. Loss of French support and erosion of tribal solidarity would throw Pontiac into exilic inhabitance of the American Bottom.

In July 1766, Pontiac signed a peace treaty at Fort de Chartres that bred resentment among Ottawa that he had overused his authority. While Pontiac’s relationships with tribespeople became fraught, and his power declined, his bonhomie with French colonists remained strong. Pontiac relocated to Cahokia, and engaged in organizing against British occupation of Illinois and the St. Louis area. French army Captain Louis St. Ange de Bellerive, whose own whereabouts and authority were challenged by the British conquest of Illinois in 1765 and the Spanish takeover of St. Louis in 1766, sympathized with his friend Pontiac.

St. Ange de Bellerive warned Pontiac of a potential assassination, but reportedly met the rebuke from Pontiac: “Captain, I am a man. I know how to fight.” On April 20, 1769 a member of the Kaskaskia tribe murdered Pontiac after the chief had been drinking in a tavern. Pontiac’s body was buried in St. Louis, near Fourth and Walnut streets downtown. Today, the sites of both Pontiac’s murder and burial are unmarked, erased places. Cahokia itself is not even the same place as when Pontiac fell; the village declined toward the nineteenth century and many early buildings were lost. Flooding hastened decline, while railroads tamped any resurgence. In 1814, St. Clair County moved its seat to Belleville, leaving Cahokia as one of Illinois’ many disempowered seats of territorial statecraft.

The Bell may be the prototype for the architectural symbols of the American Bottom: commonplace at first glance, seeming to belong to a generic American vernacular, signifiers that seem tautological in the presence of meaning. Yet The Bell is situated in a suburban landscape yet fully surveyed, whose cultural patterns and meanings are quiet perhaps only because they lack the robust historic inquiry that old Cahokia has received. The Bell also is a marker pointing elsewhere, because it is so generic. The visitor seeking meaning always already looks elsewhere when faced with such a building, so it points to relational geographic meaning that eventually may unlock its own presence. At the least, The Bell raises the consciousness needed to “find” Pontiac’s death site. A landscape of demystified objects tells no real story of the American Bottom, because the American Bottom is inherently mystified and defined by the lack (not abundance) of such objects.

National Building Arts Center (Sterling Steel Casting Company)

North of Camp Jackson Road in Cahokia, Falling Springs Road runs past the now-abandoned Parks Aviation College campus and through the crossroads business district of the village of Maplewood, now absorbed into Cahokia. Still further, the road brings into view a viaduct leading to the St. Louis Downtown Airport. Under that viaduct runs Lower Cahokia Road, a dead-ender that takes an explorer into the semi-forested brownfields of the Moss Tie Company plant, where railroad ties once were made in exponential number, and the Socony-Vacuum refinery and tank farm, last operated by Mobil Oil. These sites are brushy, verdant and toxic. The Socony-Vacuum property itself is contaminated with underground gasoline that has spread to adjacent properties. Moss Tie is a strange compound of gravel and creosote-infected ground.

Falling Springs Road once was Lower Cahokia Road, and still serves its original function of connecting East St. Louis to Cahokia. The route has been altered several times, and the landscape has passed from agricultural bottomland into an industrial panorama that includes chemical plants, a nitrogen facility, a zinc plant and a majestic view of the full St. Louis skyline. In the midst also are workers’ houses in Sauget, modestly present under vinyl siding and in plane gabled frame form; the modernist ornament-free Sauget Village Hall; an amateur baseball field; and the Metro East K-9 Training Facility along Little Avenue. Once upon a time, Little Avenue sported workers’ houses, where employees likely to work at nearby Monsanto Chemical dwelled. Today, curb cuts and phantom driveway stubs mark the locations of the houses that were removed after Monsanto realized an emission liability.

North of Little Avenue is a sprawling complex of steel-frame industrial buildings that is a weirdly anti-nostalgic repository of the nation’s largest collection of architectural artifacts. The National Building Arts Center sprawls across nearly 15 acres in a wedge-shaped site, occupying the historic foundry built in stages by the Sterling Steel Casting Company beginning in 1921. The site’s shape is forged by the road, the track path of the old Alton & Southern Railroad, and the flyby straightaway of the former East St. Louis, Waterloo & Columbia Railroad that separates the foundry site from the wild toxic forest of the Socony-Vacuum site.

Founded by William J. Shive, Sterling Steel Casting Company was one of the St. Louis region’s first all-electric sand casting steel foundries. At the time of the company’s purchase of the land, this was unincorporated East St. Louis and Monsanto’s acquisition of land was still an eye-glimmer. (Monsanto would incorporate Sauget as “Monsanto” in 1926.) Sterling Steel took advantage of a wide open site and the freight rail connection of the Alton & Southern. Records indicate that the post-East St. Louis massacre workforce was always integrated. Black and white workers labored here in the early years, while corporate records show that Mexican and black workers largely comprised the workforce when the plant closed in 2001.

Sterling Steel was part of a belt of gray iron foundries, mills and blast furnaces stretching from here into Granite City and Alton. By the 1920s, the area was dubbed the “Pittsburgh of the West,” and its output was competitive. Sterling Steel grew in phases, with its business driven by railroad, machine tool, marine and later automotive founding. The company’s early casting shed grew in increments until it became the long, low form seen today. The building’s ribbons of steel window sash are missing, along with most of its founding equipment. Three overhead bridge cranes illustrate the building’s purpose well.

Most industrial facilities of the American Bottom have faced demolition or dereliction upon closure. Not so with Sterling Steel Casing, whose plant ended up in the ownership of the National Building Arts Center (NBAC) by 2005. NBAC is a colorful operation, led by salvage expert and historian Larry Giles, whose careful work has brought together parts and wholes of building systems from St. Louis, Chicago, New York and elsewhere. Giles’ collection contains over 300,000 parts, and includes over 120 cast iron storefronts, several full building elevations, machine shops, and more. The NBAC also possesses a study library on architectural and allied arts whose contents defy the scale of the grassroots NBAC.

National Building Arts Center. Sauget, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

NBAC is not a columbarium of lost architecture, but rather a place that promotes holistic learning on how buildings work, and what craft is needed for their care. While Giles’ efforts to conserve material at the eleventh hour can be seen as desperate preservation, in fact the results compose a forward-looking collection that aims to inspire and nurture building arts in the 21st century. Perhaps the challenge of NBAC is that its intellectual stake in its own collection, and its earnest rehabilitation of a once-discarded industrial facility, are so alien to the practice of historic preservation in the United States as to require either a new definition or term. NBAC embraces David Harvey’s assertion that tourism is about becoming instead of being. Visitors here are invited into a process of knowing and sharing, not into an easy encounter with closely-interpreted objects. NBAC currently is not open to the public, and much of its collection is stored in custom crates. The volume alone speaks to the death of much architecture in Giles’ nearly 40 years of salvaging, but the keepers disavow that the resting place is a memorial site. Thus NBAC aims for hard, earnest labor atop nearly Herculean past efforts: challenging object conservation’s lethargy, and bursting historic preservation’s bias toward remaking the past into the image of the present. NBAC dares the future to be more like the past, when the building arts whose object-products it conserves were widespread living arts.

AALCO Wrecking Yard

Harry Hochman founded the still-extant AALCO Wrecking Company in St. Louis in 1932. Just off of today’s Illinois Route 3, at the exit to Eighth Street in East St. Louis, a fan-shaped landform is hugged by the curve of the street and the bends of the Terminal Railroad Association’s approach to the MacArthur Bridge and the former Illinois Central Railroad right-of- way. Decoding this site comes easier by asking “how” instead of “what.” A grass-covered drosscape in between transportation routes does not distinguish the site from any other byway remainder. Instead, the how-ness of this site emerges through contextual clues: the cleared land itself, the proximity to rail, the slopes downward at the edges. There is an implied presence, but the even grade rules out that a major building ever stood here.

This site was utilized by AALCO as a wrecking yard for decades after the 1930s, although exact dates are difficult to acertain. During the years that AALCO utilized this yard, where workers picked apart scrap metal and the company sold architectural salvage, the company was involved in clearing the St. Louis riverfront for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial. Legend holds that the company buried building material on the site to level the land, making this site a possible rival to the New Jersey dump where Robert Smithson located the ruins of Pennsylvania Station. AALCO’s work included scrapping the collection of cast iron storefronts salvaged in part of whole for the museum of American architecture originally intended for the Memorial by the National Park Service. The cast iron architecture was spared at the urging of architects Charles Peterson and John Albury Bryan as well as Sigfried Gideon. Whatever pieces of St. Louis lay here are unknown, but the placid landscape offers a compensatory memorial site. While the National Building Arts Center makes present the spolia of the lost giant across the river, this parcel offers absence for contemplation.

Bloody Island

Visitors to the East St. Louis riverfront today encounter a pleasantly unkempt area, whose form has attracted several specious plans for order that range from residential development to the scuttled CityArchRiver plans to extend the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial across the river bank. Even Eero Saarinen and Dan Kiley wistfully envisioned the western end of East St. Louis, severed from the city by elevated interstate overpasses, as a placid and monumental space. Buckminster Fuller would have domed the area as part of his Old Man River City plan in 1971. All of these plans blithely stepped over the fact that this area essentially is an overgrown sandbar once named Bloody Island.

Front Street, East St. Louis, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Today the land mass is partially riparian, with forested wetland occupying the majority of the area. The Eads Bridge approach to the north bounds a cluster of buildings at the north, including the Casino Queen complex and the venerable reinforced concrete grain silos now operated by Cargill. At the center is the inscription of monumental history, in the form of the Gateway Geyser, the Macolm W. Martin Riverfront Park, and a clean, modern concrete overlook that allows visitors to peer at St. Louis’ skyline over the levee. The riverfront park responds to the Gateway Arch, and presents a puzzling emphasis on a mode of tourism that seems asynchronous with the rugged character of the area.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, there was no land mass here – only the wide expanse of the Mississippi River. By 1810, a small sandbar was evident at the north end of the riverfront. By 1817, after the Village of Illinois (later Illinoistown and later East St. Louis) was platted, the sandbar was large enough to be named an “island” on maps. That same year, Thomas Hart Benton challenged Judge Charles Lucas to a duel, and the pair elected to stage the duel on the island. After Benton slay Lucas, the island took on the name “Bloody Island,” and four other reported duels followed.

After Bloody Island’s growth continued, the land mass looked like a permanent gulf between the emergent settlement on the Illinois side and the city of St. Louis. In 1827, Samuel Wiggins purchased the island in order to complete his control of the Illinois riverfront. Wiggins had operated the Wiggins Ferry at St. Louis since 1820, and garnered a monopoly on river transportation. By 1829, Wiggins purchases – which included all of 900 acres of riverfront behind Bloody Island – made sure that there was no competition in transferring goods across the river within two miles. Later, the Illinois General Assembly granted the Wiggins Ferry Company the right to perpetual succession in 1853, creating the largest blockage on constructing a bridge at St. Louis.

Remnant rail sidings on what was once Bloody Island. East St. Louis, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

By the 1830s, a series of bars emergent from Bloody Island threatened to close the Mississippi River channel at St. Louis to navigation. The river current shifted to the east, so that the channel between Illinoistown and Bloody Island was the only channel with a current swift enough to sufficiently stay clear of obstructive bars. The north end of Bloody Island eroded away, carried to the southern end where the Island grew further. Landing at the St. Louis wharf became a feat of courage, and the city feared its demise as a trade port. Alton, Illinois, located on a clar section of the Mississippi, began assuming that it could usurp St. Louis at the regional port. In 1837, the United States Army Corps of Engineers assigned Lt. Robert E. Lee with the task of preventing the closure of the channel at St. Louis. Lee designed a dike at the northern end of the eastern channel, which was not fully constructed until 1847. Lee’s intervention redirected the river current to the western channel, and led to the complete cessation of current to the east.

By 1865, Bloody Island was part of East St. Louis, and became its Third Ward. However, the sandy soil proved inappropriate for major construction, and East St. Louis’ urban core remained distant from St. Louis. Instead the old island became the site of a massive collection of rail freight terminals to the north and south of the Eads Bridge. One of the last major freight terminals to disappear was the warehouse, track and freight lanes built by the Big Four Railroad just south of the Eads Bridge. By 1991, the entire complex was wrecked to build the first incarnation of the Casino Queen. The Casino Queen’s generation of monopoly tax revenue was supposed to be a contemporary fix on economic vitality for East St. Louis, but its heyday ended when Missouri authorized its own casinos by the mid-1990s. Strangely, Bloody Island’s inclusion in various schemes for tourism has not laid any claims on its actual heritage. Tales of river navigation, duels among St. Louis’ elite, monopoly land ownership and the deeds of Robert E. Lee seem to present endless interpretive fodder, as well as footholds in grand national narratives. Instead Bloody Island remains the scene of economic extraction, caught up in a generic and nearly placeless monumentalism.

Downtown East St. Louis

Until the City of East St. Louis demolished the landmark Murphy Building in May 2015, there was one block of Collinsville Avenue that actually had enough physical integrity to represent the urban aspirations that propelled East St. Louis to its peak population of 82,000 residents in 1960. In fact, that block had lost no buildings until 2009, and only three before the Murphy Building fell. All around the block, however, was a tapestry of presence and absence that betrayed the fact that much of downtown East St. Louis once had the density and evident purpose as the lone block of Collinsville Avenue. Of course, not all is shuttered or lost – and downtown East St. Louis slowly hums with a small-scale economy. Denise’s Place remains a popular bar, LeAnn Fur and Leather remains in business after decades, two bank branches operate and law firms retain offices opened in proximity to the still-active, restored United States District Court House on Missouri Avenue (opened by President William Howard Taft in 1911).

Around the synecdoche of Collinsville Avenue, downtown East St. Louis offers a plethora of specimens of urban dross: a pawn shop built atop a Mississippian mound site, half-wild parking lots and open spaces, gas stations, a row of vacant fast food restaurants on St. Louis Avenue that almost composes an absurd museum collection aligned with Camilo Jose Vergara’s old proposal to make the skyscrapers of Detroit into the “Smithsonian of Decline.” More stalwart landmarks also remain, from low-rise public housing to the massive Ainad Shrine Temple (1923; William B. Ittner) to the postmodern City Hall, would-be symbol of rebirth built through literal destruction of its French Renaissance Revival predecessor. Diagonally across from City Hall sits the amazing gem called the Fountain of Youth Park, a nearly folk-art plaza with a central fountain sitting between two interstate on-ramps. Two blocks west and across the street is the empty site where the Broadway Theater sheltered black East St. Louisans escaping murderous whites in 1917 – a haven until the mob set it ablaze and its collapsed on the refugees. The park’s cheery amateur form resurrects the tragedy through omission. As with much of the American Bottom, this site of absence invokes the presence of unresolved memory.

Looking East Southeast down Missouri Ave. East St. Louis, IL. Photo by Jesse Vogler

Yet the intersection of Collinsville and Missouri avenues offers the vantage that reaches to high achievement in architectural place-making, instead of the indeterminacy of the surroundings. The group of buildings in this area actually formed a National Register of Historic Places historic district listed in 2014. The Downtown East St. Louis Historic District encompasses two city blocks along Collinsville Avenue, one and a half blocks along Missouri Ave, and the south side of one block along St. Louis Avenue. There are 44 sites in the district, 35 of which had buildings on them at listing. Since the Murphy Building was demolished, three other buildings across the street fell to the wrecking ball.

The District occupies a small portion of East St. Louis’ area, yet it represents the center of what was historically a very large and vibrant commercial zone. The boundaries of the District encompass an area that, while fractured by vacancy and demolition, represents the most intact urban corridor remaining in the city. The clear and defined edges of the District mark a division between the intact/cohesive and demolished urban fabric. Large parking lots and alleys enclose all sides of the District. Parking lots also frame the buildings within the district, as the majority of storefronts along Collinsville have rear-access parking that is accessed off alleys. The result of these parking lots and alleys is a clear visual and sensatory separation between the street front along Collinsville and Missouri Ave and the surrounding area.

Between East St. Louis’ incorporation and 1960, East St. Louis’ downtown business district developed in an area presently bounded by Broadway, Third Street, St. Clair Avenue and Tenth Street. The distance from the Mississippi River was necessitated by the presence of Bloody Island, which was unsuitable for substantial construction and prone to flooding. After Bloody Island had been connected to the bank, the Wiggins Ferry Company hired the St. Clair County surveyor in 1865 to survey and lay out 734 town lots as the “Ferry Addition of East St. Louis.” This area never fully developed, and eventually became the site of rail terminals and their yards, keeping commercial development set back from the river.

At the end of the Civil War, business interests looked to East St. Louis as a logical outpost of railroad terminals and manufacturing facilities adjacent to St. Louis. The city’s first real bank was the East St. Louis Real Estate and Saving Bank, founded in 1865 and later known as the East St. Louis Bank. The East St. Louis Real Estate and Saving Bank located south of the District at Third and Broadway, in a cluster of commercial buildings. One observer proclaimed as early as 1865 that: “East St. Louis was losing its rural ambience and was well on its way to becoming the second largest city in the state of Illinois.”

Yet the largest deterrent to East St. Louis’ downtown development in the 19th century was flooding, dramatized by a major 1844 flood of the bottomlands where East St. Louis would rise. When the Eads Bridge opened in 1874, it logically opened development of downtown parcels now easily accessible to St. Louis. Yet the Bridge deposited carriages and omnibuses onto low-lying streets that frequently flooded or remained muddy. In 1875, Mayor John Bowman secured passage in the city’s Board of Aldermen of the city’s first “high grade ordinance,” which raised some streets 12 to 20 feet above existing grade and the Flood of 1844 high water mark. However, opponents fearing tax increases successfully filed petitions in court that delayed implementation of the ordinance.

Historian Bill Nunes writes that the first “high-grade buildings” rose in 1876. Seven years later, in 1883, a large fire starting at the intersection of Division and Collinsville avenues destroyed 22 houses and number of businesses. This fire spurred commercial development on the blocks within the District. Meanwhile, East St. Louis’s population would rise from 9,185 in 1880 to 29,734 in 1900. Development of the downtown area was a key issue in the mayoral election of 1887, with victorious candidate M.M. Stephens championing raising the downtown street grades further. Proponents of raising the street grades generally represented corporate and real estate interests, while opponents were local politicians. Stephens pushed through a $725,000 bond issue in 1887 that funded raising Front Street above the 1844 high water mark, so that it could become a levee, and funds to raise principal streets 14 to 20 feet higher. Beginning in 1888, downtown streets were raised. Collinsville Avenue was raised in 1889, despite some opposition from property owners. That same year, East St. Louis had 14,272 residents, was noted as the fastest-growing city in the nation, laid its first electric streetcar tracks and published the first issue of the East St. Louis Journal, a new daily.

The raised streets enabled development of new buildings, and businesses boomed. The East St. Louis Bank became First National Bank in 1890, with expanded lending power. First National and other institutions quickly funded real estate development. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted in an August 1892 article that “handsome business blocks” lined the raised streets of Main, Collinsville, Missouri, Broadway and Third. The article notes that new commercial buildings had replaced vacant lots and houses on those streets. Collinsville Avenue had been raised from Broadway to St. Clair Avenue and had an electric streetcar line; this was the “principal business street of the city” according to the reporter. Within the District, Missouri Avenue was lagging behind Collinsville Avenue in new construction but the reporter suggested that it would catch up.

A natural disaster brought rapid change to the emergent business district. A great tornado on May 27, 1896 devastated East St. Louis, causing more than $2 million in property damage and killing over 100. The tornado first hit the ground in St. Louis, and passed across the river along the Eads Bridge. The devastation concentrated downtown, where City Hall was destroyed along with buildings on Missouri Avenue, Main Street and Collinsville Avenue. Along with the street grade changes, the tornado was responsible for reshaping the downtown area. Today, what remains on Collinsville Avenue represents the trajectory of these events’ consequences: an urban core, that later lost its reason for being only to settle into a slower and different economy. This is not really the city’s downtown today. What is Collinsville Avenue now? That question has only a set of possible answers in the 21st century.

Armour Packing Plant

In April 2016, a wrecking crew used dynamite to destroy the refrigeration plant and boiler house at the former Armour & Company packing plant. The loss of the iconic building, whose two smokestacks could be seen for miles, meant the end of physical evidence of the large packing plants that once were located in the National City Stockyards. In fact, the demolition also spelled the near complete loss of physical traces of the stockyards, whose stories now are left to be told by an old office building, the now-closed Packers’ By-Products Company building on Route 3, some street names and successor industries located in newer facilities scattered around the site. The ramps for Interstate 70 built after 2009 now bury much of the land mass, and break up its potential legibility.

That an entire industrial center could be erased is symptomatic, not aberrant, to American capitalism. Rail-served stockyards and vertical packinghouses belong to the late 19th century, while today’s system of interstate-connected confined animal feeding operations and horizontal truck-served packing houses belong to the late 20th. The interval between witnessed a spectacular rise and fall at National City, Chicgao’s Union Stock Yards, Omaha and other sites around the nation.

The “Saint Louis National Stock Yards” opened in 1873. The original livestock market occupied 100 acres of the site and allowed for railcar loading and unloading. In 1874, the yards accommodated 17,264 cars containing 234,002 cattle, 498,407 sheep and 2,235 horses. By 1880 the numbers grew to 38,294 cars containing 346,533 cattle, 1,262,234 hogs, 129,611 sheep and 5,963 horses. By 1874, two small meat-processing plants were in operation on adjacent land. However, it would be another 10 to 20 years before major meatpackers establish plants near the stockyards, as they had already done in Chicago. In 1880, major industries located at the National City Stockyards included the McCarthy Live Stock and Packing Company, Francis Whitaker & Sons, the East St. Louis Packing and Provision Company, Carey’s Beef and Pork Packing House, George Mulrow & Company, Pork Packers, the St. Louis Rendering Works, the St. Clair Rendering Company and the St. Louis Carbon Works. The first large plant to be built was a plant built for Hunter, Evans & Company in 1884 (sold to Nelson Morris & Company five years later). Swift arrived in 1893, and Armour opened a large plant in 1903. The “Big Three” packers—Morris, Swift, and Armour—operated alongside a few other smaller companies. Circa 1910, the area’s meat processing facilities covered approximately 6 acres and 2,500 people.

In 1907, the stockyards and surrounding areas were incorporated as National City. The St. Louis National Stockyards Company arranged for the construction of 40 worker houses—the minimum number necessary for incorporation—over an area of two blocks and established a mayor and city council. The company town’s population would eventually grow to 244 people in 1940. Incorporation allowed the stockyards and associated meatpacking companies to organize and operate without taxation or other local legal restrictions. By the 1950s, National City peaked with record hog slaughter numbers placing it as the “hog capital” of the nation. The profitability of the stockyards was declining, however, and the packing houses started closing up shop. Nelson Morris had already closed in 1935, while Armour closed in 1959, Swift closed in 1967 and Hunter closed in 1981. Gone with these plants was a workforce that had peaked at over 10,000 in the plants alone.

The Armour plant became a special totem of the stockyards’ diminution, as a plant whose remaining sections had been abandoned longer than they were ever used before their demolition. By 2016, Armour and Company Packing Plant consisted of four buildings in conditions ranging from stable to ruinous. The four buildings were: a four-story boiler house/refrigeration plant with two tall brick smokestacks, built in 1902 and modified in 1917 and 1950 (a fragment of a conveyance structure stands adjacent but not connected); a five-story hog killing, packing and storage building built in 1902; a one-story electric substation built ca. 1950; and a three-story supply warehouse built ca. 1950. These buildings attracted photographers, journalists, urban explorers and industrial archaeologists from around the world. In the ruinous state, the Armour plant provided the opportunity for a counter-tourism venerating what the buildings had become, rather than mourning their passage from productivity.

Armour and Company began construction on its National City Stockyards plant in 1901. In 1903, the East St. Louis Daily Journal reported that Armour and Company was opening its massive new plant at the National City Stockyards. The plant covered 23 acres and contained 18 buildings, with 50 acres of floor space. Over 13 million bricks were used to build a plant that included purpose-built buildings for sausage production, egg and poultry processing, ham production, ice making and box manufacturing. Armour and Company could handle every aspect of its production including boxing and shipping under its own roofs, using its own resources. This model embodied the practice of vertical integration of the supply chain, avoiding the use of contractors. The plant layout, designed by architect John W. Foster, arranged production in two 660-foot-long rows of buildings joined to the National City Stockyards pens directly by a series of reinforced concrete conveyance lanes.

After the plant’s closure, the Stockyards Company took possession, and wrecked the longest row of packing buildings and the office building. The boiler house was used to produce electricity at least until 1986, but the remaining buildings were ruinous by the 1990s. Some people suggested that the boiler house and refrigeration plant, with its original De La Vergne stationery compressors, could be preserved as a sort of industrial museum. Yet the Armour ruins defied conventional heritage claims. Anyone claiming the Armour ruins as worthy of conservation confounded Nietzsche’s assertion of three modes of modern history – monumental, critical and antiquarian – as well as J.B. Jackson’s theory of the cycles of ruin and purification that dominate American preservation. At the same time, documented encounters of exploration of the plant (including a man called “White Rabbit” who climbed to the top of one of the smokestacks) was far from scenographic. The Armour remains presented an artifact that was the subject of a mode of history yet unnamed.

Venice Power Plant

On the south side of the McKinley Bridge approach there is an electric power plant. Today, the facility consists of two natural gas burners and a grid of electric transformers. Along the levee wall, however, a long flat gravel-paved area presents a question. Since the plant’s small fleet of vehicles is parked elsewhere, why does this large paved expanse even exist? The answer: The gravel rectangle marks the site where the massive Venice Power Plant stood until it was wrecked in 2012. Beneath the gravel may be footings and some subsurface remnants. Above ground, however, emptiness.

The location is no coincidence, since the original Venice Power Station was built by the Illinois Traction Company in 1910 to provide current to the electric interurban street car line that utilized the McKinley Bridge (which opened in 1911). Eventually, the Illinois Traction Company ended up in the possession of Samuel Insull’s giant Illinois Power & Light Company. Illinois Power & Light Company sold the plant to St. Louis’ Union Electric Light & Power Company in 1927, while buying back some of the electricity generated there.

Union Electric wrecked the original power plant and built a massive, volumetric, red brick Art Deco station that opened in 1942. The first two coal-fired sections of the plant to open each generated 80,000 kilowatts, and eventually the station grew to six sections (with accompanying smokestacks, that were long gone by 2012). Soon, Union Electric added ash ponds to the plant, that were later filled in. By the mid-1970s, the plant was converted to burn natural gas and oil. Eventually the plant’s form provided obsolete, and the freestanding burners were built while the plant was shuttered. The form of the plant, however, once dominated views from all sides, and demonstrated the integral relationship between the bridge and electric power infrastructure. Today, the bridge carries automobiles and a smattering of cyclists and pedestrians, and the power plant site is empty. The relationship is best encountered in historic record, or by curious gazes.

Merchants Bridge Railroad Approach

The Illinois Traction System began assembling land and expanding track to bridge its interurban electric rail system to St. Louis as early as 1906. While the ultimate vision of connecting St. Louis to Chicago never came to pass, an infrastructural system emerged the was akin to a heart (St. Louis) attached to veins and arteries (tracks into central Illinois). Today parts of the system remain legible as rail right of way, while other elements are concealed. Crossing Route 3 just east of the Venice Power Plant site is an element at once legible and concealed. Aerial photography shows a diagonal strip of wild green running between carefully tilled farm fields, with the impact validating John Stilgoe’s imperative for explorers to follow “traces” of lost infrastructure across the land to divine economic and settlement histories.

Here, the diagonal – punctuated by a set of the stagnant concrete piers at Route 3 – marks where the Illinois Traction System built a massive and picturesque rail approach from the McKinley Bridge to the rail yards between Venice and Brooklyn. This approach served freight traffic, while the passenger cars ran on a trestle into Granite City. The long approach was an anachronism until its demolition in 2008, because it consisted of a timber structure save the piers at the state highway (a later alteration). The heavy pine timbering supported a single, unbounded rail that allowed the Illinois Traction System to avoid interaction with the historically-dreaded Terminal Railroad Association.

In the last years, the approach was defunct and deteriorating. Timbers collapsed, leaving the twin steel rails sagging across an abyss in one section. Yet the rail infrastructure evinced the desperate and steady development of railroad infrastructure across the American Bottom, as well as St. Louis’ crucial role in the economic history of the land. The surviving disruption to the land serves to tell at least part of that story.

National Enameling And Stamping Company Works

German immigrants Frederick G. and William F. Niedringhaus played a major role in St. Louis history by organizing the industrial city of Granite City, and a major role in American industry by pioneering the process of creating durable, affordable stamped and enameled metal-ware. The brothers had founded the St. Louis Stamping Company in 1866, and by 1871 had started construction of a still-extant factory in St. Louis where they deep-stamped tin kitchenware, and built an adjacent rolling mill. The brothers saw limitations to enameled kitchenware, and sought to improve its performance in American cooking, which utilized gas stoves made of iron. They came up with a process in which a sheet-iron body was coated in highly vitrified glass in 1874, and patented “granite ironware,” sheet iron stamped and coated to resemble granite, in 1876.

In 1888, Frederick G. Niedringhaus successfully sought election to the U.S. Congress as a Republican from the Eighth Congressional District of Missouri and served one term from March 1889 until March 1891. Niedringhaus had basically run for the office to secure steep tariffs against foreign tin plate, to secure the dominance of American companies like his own. Niedringhaus aided passage of the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890, which raised the duty on tin plate from $22.40 to $49.28 per ton. Two months after passage of the act, the Granite Iron Rolling Mills began to produce tin plate. By 1890, employment at the stamping plant rose to 900 workers. Upon his return to St. Louis, Frederick joined his brother in seeking a new site for the company’s operations. The first plan was to expand near the stamping plant, but with the Rolling Mills’ use of the Bessemer process for steel production, which required significant amounts of coal, two problems arose: St. Louis’ nuisance emission laws, and the “arbitrary” fee on coal cross the Mississippi River set by Jay Gould on the Eads Bridge. The brothers cast their eyes eastward to the American Bottom, which had ample open land, proximity to coal, little impeding civic government and railroad infrastructure supported by the Illinois General Assembly (Missouri was slow to use state funds on rail development even after the Civil War).

William Niedringhaus and his son George, whom many historians consider the driving force behind the land search, set out in August 1891 to survey lands just northeast and across the river from their stamping works in St. Louis. They visited the small town of Kinderhook (also known as Kinder) on the so-called Six-Mile Prairie in Madison County, Illinois. The improved road access led more farmers to the area, and eventually small towns like Kinderhook appeared on the prairie. Perhaps the biggest economic boon, however, came in 1856 when the Terre Haute and Alton Railroad built tracks south from Alton to East St. Louis across the land that would become Granite City. Without a rail bridge to St. Louis, this railroad terminated at Wiggins Ferry on the East St. Louis waterfront, from which train cars crossed into St. Louis via ferry. This situation changed little when the Eads Bridge was completed, due to railroads’ not being able to obtain Missouri licenses needed to cross the river and later due to monopoly control of the bridge. The Terre Haute and Alton line finally obtained a river crossing when the three-span truss Merchant’s Bridge opened in May 1890.

Still, the area was very rural when the Niedringhaus family began to explore it. When they returned in 1892 to visit, they hired Kinderhook village schoolteacher Mark Henson as their land agent and scout. Henson obtained options on around 3,500 acres of land for the family, and they completed their purchase in 1893. they immediately set out to plan and built their new city, which the brothers infused with progressive ideals envisioned not as the conventional “company town” but a real city where residents might be factory workers but would buy their own lots and raise their own homes as they saw fit. William had studied Pullman, and thought that a more libertarian model would lead to a city that could be successful no matter what the St. Louis Stamping Company’s fate. The family’s deliberation over the name favored Granite City, the suggestion of patriarchs Frederick and William honoring the family’s product, over the less modest name of Niedringhaus offered by other family members.

By the end of 1893, the city had a plan designed by the city engineer of St. Louis. The design was inspired by that of Washington D.C., where Frederick Niedringhaus has just served in Congress. The brothers asked for an east-west thoroughfare diagonally crossing the city’s grid like Pennsylvania Avenue in the District of Columbia. On this street they would bestow family name. They also planted over 14,000 trees along the city’s new streets within two years of purchasing the land. Not all was progressive, though: blacks had to leave the town at sunset, and many black workers settled in nearby Lovejoy (now Brooklyn); the city charter forbade taverns; the Niedringhaus brothers made an estimated $4.8 million selling residential lots that had required $568,000 to purchase.

In 1895, the family hired noted St. Louis architect Frederick C. Bonsack to design new plants: one for the St. Louis Stamping Company, and another for a steel rolling mill to supply the stamping works. The new plant for St. Louis Stamping comprised 30 acres and produced graniteware and galvanized ware (among other products) for pots and pans, foot baths and gold miners’ pans. Bonsack designed a wonderful four-story office building in the Romanesque style, featuring a wide Richardsonian arched entrance under a small tower. Within seven years, 1,200 people would be employed there. By the end of the year, the family opened the Granite City Steel plant that today is part of US Steel. The plant contained two 22-ton open-hearth furnaces and four mills capable of producing 20,000 gross tons of finished product annually. This facility was needed to supply rolled steel sheets to the stamping company. Originally, the plant only made the sheets but in 1905 diversified its output. By 1908, the plant made 4 tons of bar steel and tin plate daily, employed 2,000 men and covered 15 acres. The St. Louis plant would remain active until 1912, when the family closed it.

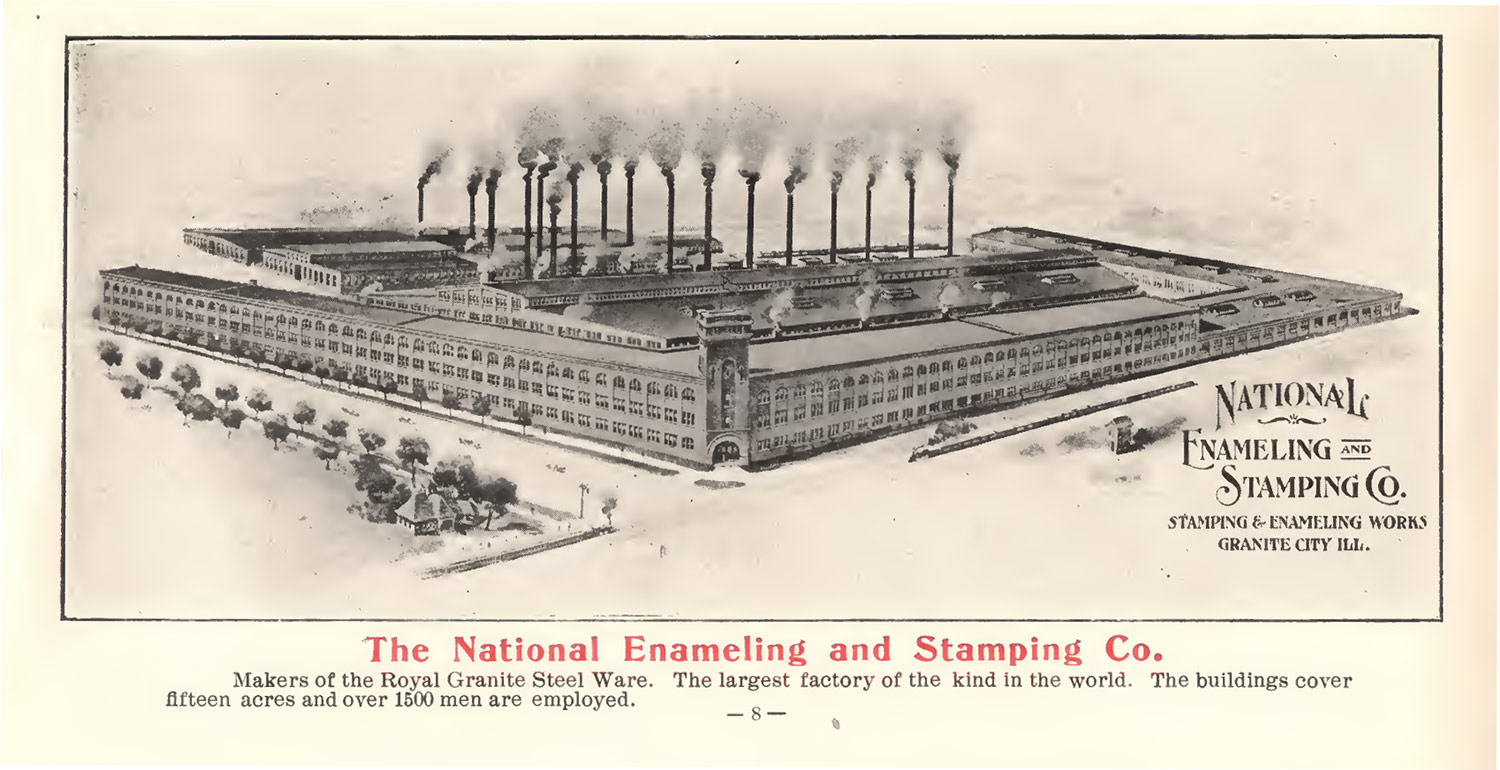

National Enameling and Stamping Company plant. From Granite City Real Estate booklet.

In 1899, the Niedringhaus family’s growing national reputation enticed them to rename their stamping company the National Enamelling and Stamping Company, or NESCO. NESCO kept its main office in downtown St. Louis, and founding brothers Frederick and William never moved to the city, instead residing in fashionable West End mansions. By the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, about ten years after Granite City was founded, the stamping works covered 1.25 million square feet on 75 acres of land and employed 4,000 persons. With its hundreds of jobs for skilled and unskilled laborers, the city became a magnet for immigrants. The first wave of immigration came to work at the NESCO plant and steel mills, and largely consisted of Welsh and English immigrants. Many Polish families migrated from St. Louis around 1900, followed by Slovaks, Greeks, Croations and Serbs who largely worked at the Commonwealth and American steel foundries. Later waves of immigration included Macedonians, Bulgarians, Romanians, Russians, Lithuanians. Finally, Mexicans arrived during World War I to take the place of conscripted laborers.

In 1924, NESCO had $30 million in assets, covered 75 acres and had a plant floor space of 1.25 million square feet. The company was employing 4,000 people. By 1930, the city’s population had risen to some 25,000 people. NESCO came up with yet another innovation in the 20th century, when it developed the single-coat-enameled NESCO Royal Graniteware. Yet the product’s appeal would wane. Granite ironware could barely compete with aluminum cookware, Pyrex, Corning Ware and stainless steel as they were developed and mass marketed from the 1930s onward. NESCO enjoyed some success during World War II, when it produced helmets and “Blitzkrieg” cans for the US government. These cans held fuel or water and floated in water with all but the top quarter inch underwater. These almost-invisible cans made delivery of provisions at sea much easier for the US Navy.

In 1956, NESCO closed its doors after declining sales faced with inexpensive, trendy aluminum cookware. Sadly, in November 2003 a huge blaze destroyed most of the remaining NESCO buildings. The buildings, mostly of mill method construction, had been used for warehouse space since 1956. By 2003, over 10,000 tires were stored in the buildings; the tires along with propane tanks allowed the fire to quickly spread out of control. Firefighters spent 14 hours battling the blaze, and the damaged buildings were immediately demolished. One four-story section of a building still stands along with a few smaller buildings. The rest of the site is fenced, and serves as home for a collection of historic rolling stock. While the plant outline is evident from aerial views, from the ground, it is almost as if the plant had never stood at all.

Granite City Art and Design District

Downtown Granite City anticipated an urbane form that was mostly realized by the 1930s. Block after block of two-part commercial buildings, banks, churches, civic buildings, corner taverns and even a few office blocks filled in the grid that the Niedringhaus brothers believed would emulate that of the national capital. Always looming here would be the giant rolling mills and furnaces of the plant today operated by United States Steel – a facility with an annual capacity of 2.8 million net tons. Lately the real shadow cast by the plant comes from its labor force participation rate, which has dropped as the plant has idled or closed parts. In 2015, United States Steel threatened to idle the whole works, with its workforce of 2,080. By December, layoffs began. The plant could be fully idled by the end of 2016, rupturing Granite City’s labor market in a way unknown ever. The reason for the city’s existence could be over, or never return to full force. A whole network of relations, including architectural forms, will change.

United States Steel cited trade agreements and tariffs as impediments to its competition, invoking externalities that plagued the Niedringhaus brothers so much that they founded their own city in the first place. Changes in the gray iron steel industry already led to the closure of Commonwealth Steel Company, whose mammoth vacant casting shed stands at the city’s entrance from Route 3. Still the United Steelworkers of America Local 1899 holds down at the Tri-City Labor Temple, a robust three-story former fraternal lodge on State Street in downtown Granite City. This building stands just a block from the blue-paneled, monolithic mid-century modern office building where US Steel’s local offices are housed. Built in 1958 by Granite City Steel Company and designed by St. Louis engineering firm Sverdrup & Parcel, the “Granite City Steel Building” anchors the downtown. While labor and industry have strong footholds with imposing buildings, the surroundings reflect a downtown marked by vacant storefronts, empty lots, fast food restaurants and a notably slow pace.

Enter the Granite City Art and Design District (GCADD), an effort launched in 2015 by landscape architect and Granite City resident Chris Carl and St. Louis community development specialist and arts organizer Galen Gondolfi. Carl and Gondolfi essentially purchased one side of the 1900 block of State Street, and transformed the shuttered buildings and vacant lots there into a set of interlocking contingent spaces for presenting visual, sculptural and performance art. Already openings have become a regional draw, bringing many St. Louisans to Granite City for the first time. Whether GCADD represents that first “creative class” spark on the cycle of gentrification that is rote for American cities, or simply an embodiment of Jane Jacobs’ imperative that new ideas need cheap, old buildings, has an unresolved answer.